Crowded Coasts Put 1 in 10 Americans at Risk for Floods, Other Hazards

Older Adults, Communities of Color, and Renters Are Especially Vulnerable

Date

May 2, 2024

Authors

The number of Americans living in the low elevation coastal zone (LECZ)—an area often at high flood risk—increased sharply between 1990 and 2020, from 25.5 million to 34 million people. Now one in every 10 people in the United States live in the LECZ.1

Population growth in the LECZ means that more people are exposed to coastal hazards, and many don’t have the resources to move or pay for repairs caused by damage from storms and flooding.

Some groups are at more risk than others. Urban dwellers, people of color, and older adults are overrepresented in the LECZ. For example, about one in five urban Black residents live in this zone, a higher share than any other group.

In our new study, we used the finest-resolution data available, census blocks, to compare trends and characteristics of people in coastal areas inside and outside the LECZ. A block is classified as being in the LECZ if any land area is continually adjacent to the coast and at 10 meters or lower in elevation.

Pinpointing the communities that are most vulnerable can help policymakers and planners develop strategies to address the effects of climate change.

Black and Hispanic Renters in Urban Areas Are Among the Most Vulnerable to Flood Risk

Urban residents around the world are more vulnerable to sea-level rise and related coastal hazards, and population growth and urbanization are putting more people at risk. In the United States, population growth in the LECZ was driven mainly by growth in the urban population, which rose a whopping 38% between 1990 and 2020, from about 22 million to 31 million.

In 2020, nearly half (48%) of all people in the LECZ lived in 25 counties (figure). Alone, Miami-Dade County, Florida, accounted for 7.5% of the U.S. population in these exposed areas. Two of the counties had smaller populations in 2020 than in 1990 (Jefferson and Orleans Parishes in Louisiana), but all others saw their populations grow.

Figure. Half of Americans in the Low Elevation Coastal Zone Live in Just 25 Counties

Top 25 U.S. Counties With the Most People Living in the LECZ (2020)

Source: Daniela Tagtachian and Deborah Balk, “Uneven Vulnerability: Characterizing Population Composition and Change in the Low Elevation Coastal Zone in the United States With a Climate Justice Lens, 1990–2020,” Frontiers in Environmental Science 11 (2023):1111856.

Disaster relief efforts often focus on homeowners because they tend to be less mobile than renters. However, lower-income renters are especially vulnerable in areas prone to flooding or other coastal hazards, partly because they tend to have fewer financial resources than homeowners. For example, when Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2000, renters and lower-income households were more likely to have their home suffer damage classified as “major” or “destroyed” than homeowners and higher-income households.

In the coastal states in our study, Black and Hispanic residents were much more likely to rent their homes in 2010 (55% and 53% respectively) compared with their white counterparts (30%). This racial disparity in housing was even more pronounced in the LECZ, where Black and Hispanic residents were nearly twice as likely as white residents to be renters in urban areas.

In addition to the general economic precarity of renting, extreme weather events can have compounding effects, often augmenting their vulnerability. During Winter Storm Uri in Texas, people who were Black, renting, and who had children endured longer power outages, and Black people experienced longer water outages.

The Number of Older Americans Living in Low-Lying Coastal Areas Has Increased Sharply

Older adults are more vulnerable to the effects of flooding and other coastal hazards, not only because of their higher disability rates, but also because they often live in lower-income communities with older housing stock. Many older adults can’t afford to invest in retrofits to protect their homes from flood damage, and some older homes are exempt from new building codes that provide this protection.

Nearly 20 years ago, Hurricane Katrina provided a stark example of this vulnerability. While people over age 60 represented just 15% of the population of New Orleans in 2005, they accounted for more than 70% of the deaths caused by the historic storm.

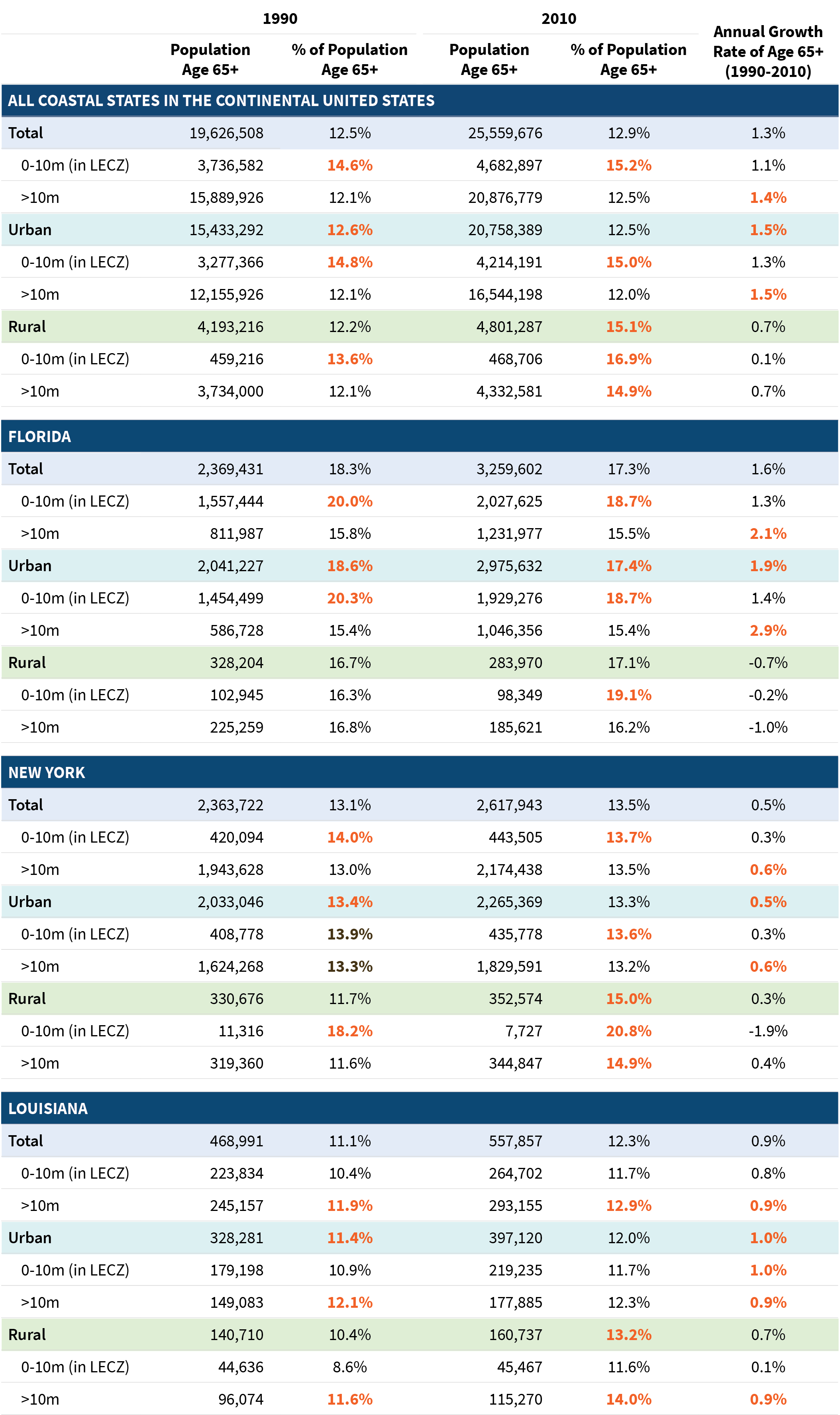

In our study, people ages 65 and older made up a larger share of the LECZ population (15.2%) than those living in other coastal areas (12.5%). The gap in the share of older adults was even wider between urban areas in the LECZ (15.0%) and urban areas elsewhere (12.0%).

In addition, 1 million more older adults lived in the LECZ in 2010 (4.7 million) than in 1990 (3.7 million), putting more older Americans at risk of enduring floods and other coastal hazards. Florida alone added 470,000 older adults in the LECZ during this period (table). Two other states with disproportionate exposure to coastal hazard—Louisiana and New York—also have large populations of older adults, but they haven’t grown as rapidly.

Table. The Number of Older Adults in the Low Elevation Coastal Zone Jumped Sharply From 1990 to 2010, Especially in Florida

Growth in the population ages 65 and older in the LECZ in Florida, Louisiana, New York, and all coastal states in the continental U.S., 1990–2010

Note: Orange values are above average for that location.

Source: Daniela Tagtachian and Deborah Balk, “Uneven Vulnerability: Characterizing Population Composition and Change in the Low Elevation Coastal Zone in the United States With a Climate Justice Lens, 1990–2020,” Frontiers in Environmental Science 11 (2023):1111856. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1111856.

Climate Planners Can Reduce Inequities by Including Vulnerable Populations in Mitigation, Assistance, and Recovery Efforts

This research can be used by planners to implement climate adaptation, mitigation, and recovery strategies that are equitable and protect the people who face the greatest risks. For example, planners should note racial disparities in homeownership and renter rates and the particular vulnerability of minority communities and older adults to coastal hazards, simply by virtue of living in the LECZ.

There are several steps that planners can take to help meet the needs of vulnerable communities:

- Disaster relief efforts should focus on minimizing financial and housing instability—and not base decisions solely on appraised home values, which reinforces current social inequities by focusing on restoring wealth.

- Vulnerable older residents should be part of resiliency planning, housing policy, and corresponding emergency care and disaster relief services.

- Climate planners should consider how people in urban and rural areas may have different exposure to flood risk and other coastal hazards.

- Vulnerable populations should be included in all aspects of climate planning—from data collection and analysis and stakeholder engagement to decisionmaking processes and policy proposals.

At a minimum, climate adaptation and mitigation policies should not make existing inequities worse. By using a social equity lens, planners can ensure that policies designed to help us adapt and respond to the growing threat of climate change meet the needs of the most vulnerable communities.

For data for your community, download the results from CUNY.

Daniela Adriana Tagtachian is a doctoral student in sociology at the Graduate Center at the City University of New York (CUNY) and a Demography Fellow of the CUNY Institute for Demographic Research. Deborah Balk is a Professor in the Marxe School of Public and International Affairs at CUNY and the CUNY Graduate Center and Director of the CUNY Institute for Demographic Research.

References

- Daniela Tagtachian and Deborah Balk, “Uneven Vulnerability: Characterizing Population Composition and Change in the Low Elevation Coastal Zone in the United States With a Climate Justice Lens, 1990–2020,” Frontiers in Environmental Science 11 (2023):1111856. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1111856.