Paola Scommegna

Contributing Senior Writer

Income, neighborhood characteristics, and state policies may underly racial disparities in who gets needed care, despite federal efforts to expand home-care programs.

March 21, 2024

Contributing Senior Writer

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) included provisions to expand community and home-based services for older adults, research shows that Black and Hispanic older adults are much more likely to need daily help at home—and to go without it—than their white peers.1

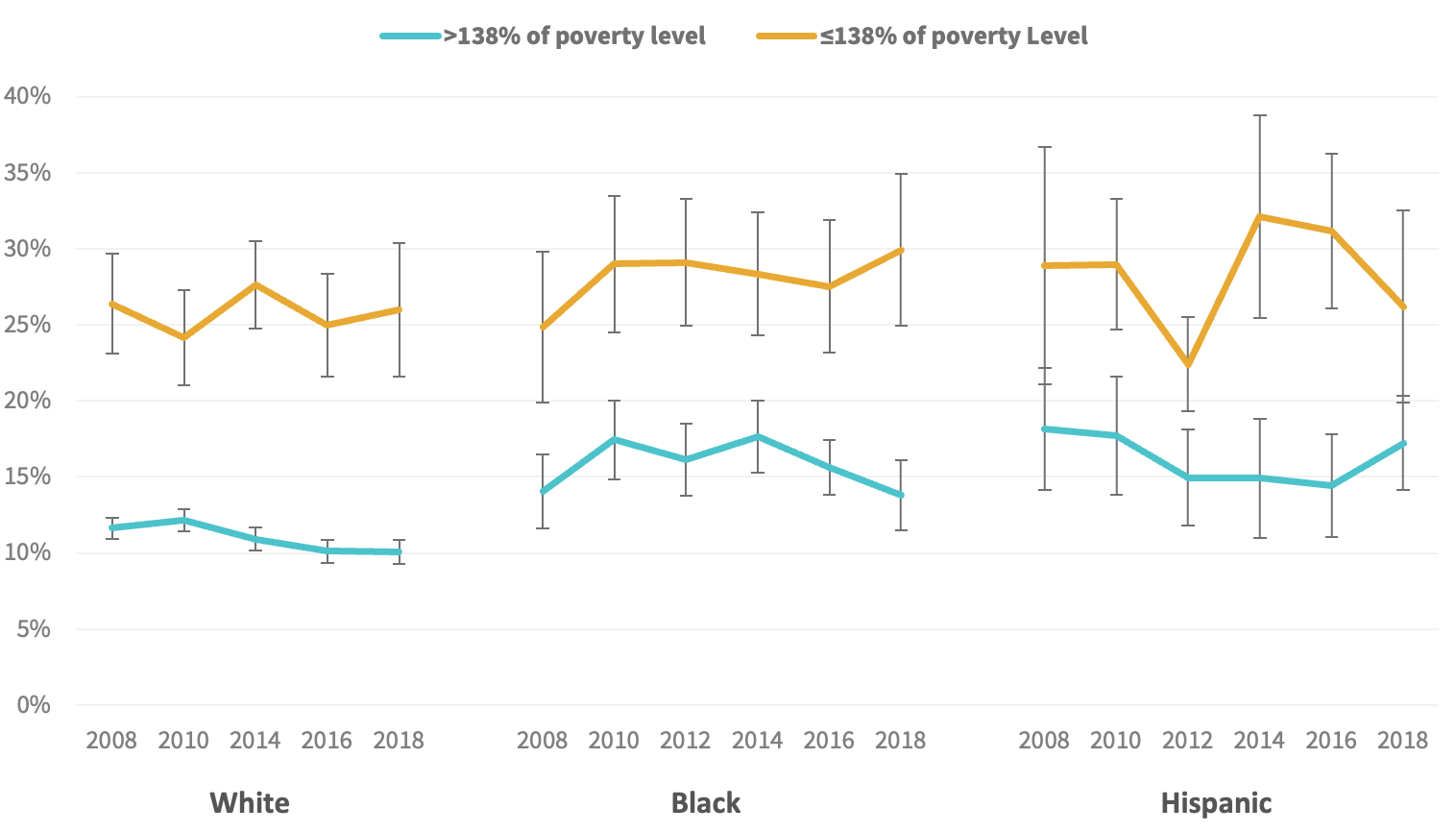

About 1 in 3 Black and Hispanic older adults had difficulties at home with daily tasks such as showering, dressing, or preparing hot meals compared with 1 in 5 older white adults, finds a new study by Jun Li of Syracuse University and Jinkyung Ha and Geoffrey Hoffman of the University of Michigan. The researchers used data from 2008 to 2018 from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study.

Black and Hispanic older adults ages 55 and above who need help with daily activities were consistently 1.5 times more likely to be without corresponding care support than older white adults, Li, Ha, and Hoffman found. Yet they were no more likely than older white adults to receive paid help, instead relying heavily on family and friends.

However, these racial and ethnic gaps were not present among lower-income older adults, who had high levels of unmet need for care, regardless of their race (see figure).

Source: Jun Li, Jinkyung Ha, and Geoffrey Hoffman, “Unaddressed Functional Difficulty and Care Support Among White, Black, and Hispanic Older Adults in the Last Decade,” Health Affairs Scholar 1, no. 3 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/haschl/qxad041

These differences between groups were consistent over time, despite ACA provisions—enacted in 2010—that sought to expand home and community-based care to enable lower-income older adults to remain in their homes rather than move to more costly residential care facilities.

“I was surprised by the prevalence of people with unmet needs who were not getting care support. Given all the hopes that we had with trying to equalize disparities [by expanding] many home and community-based services, we’re still seeing these high rates,” said Li.

Black and Hispanic older adults’ heavy reliance on family and friends for care may “have some costs down the road for their caregivers,” Li noted. “While family caregivers provide essential services, much of their labor and sacrifices are invisible, taking an often underrecognized toll on their physical and emotional health. Many juggle the demands of their jobs along with caregiving.”

The familiar realtors’ mantra, “location, location, location” also appears to affect the support available to America’s older adults with disabilities and contributes to racial and ethnic disparities in who gets help. The place these older adults call home makes a difference in the assistance they receive and how satisfied they are with their lives, more new research shows.2

More than a dozen neighborhood characteristics and state policies help shape the likelihood that older adults will have the care and support they need, a nine-member team led by Chanee Fabius of Johns Hopkins University found.

Their analysis showed that living in a disadvantaged neighborhood with higher poverty, unemployment, and public assistance use and less neighborhood cohesion (limited trust and assistance among neighbors) was related to older adults experiencing the adverse consequences of going without care (see table). These negative effects can include missed medication, sitting in soiled clothing, skipping meals, or being unable to get out of bed because no one was there to help.

The research team linked state policies that limit the availability and generosity of health care and social services to a higher risk of older adults with disabilities having participation limitations, such as not being able to leave their homes to visit family or friends or attend religious services or other events for health reasons.

Older adults with disabilities more frequently reported experiencing negative emotions such as sadness, boredom, or dissatisfaction if they lived in neighborhoods with low social cohesion and lower housing values relative to incomes (often a sign of neighborhood poverty), as well as areas where direct care workers had lower wages, the researchers found.

To identify these patterns, the researchers combined data from multiple sources including individual reports from older adults with disabilities from the nationally representative National Health and Aging Trends Study and census-tract level features of neighborhoods from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. They drew relevant measures from the county and state levels from a variety of sources, such as the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, and the AARP LTSS Scorecard.

“The main takeaway is that place matters,” explained Fabius. Her team developed a framework that provides a comprehensive view of how the care-related aspects of the local environment contribute to the quality of life of older adults with disabilities.

Their findings underscore the importance of policies, practices, and investments—such as states allocating funds to Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services or ensuring direct care workers receive a living wage—in meeting the care needs of older adults with disabilities, the researchers said.

The research team noted that the strong relationship between living in a disadvantaged neighborhood and having unmet care needs is not something that can be addressed quickly without sustained financial investment. And for older adults with lower incomes or who are racial or ethnic minorities—who face disproportionately high levels of disability—living in a disadvantaged neighborhood may compound the obstacles to care, they suggested.

In Fabius’ view, their findings related to disadvantaged neighborhoods highlight the value of using specific interventions to help people based on their particular needs. She pointed to the example of Community Aging in Place—Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE), a program that enables lower-income urban older adults with disabilities to build the skills needed to live independently in their homes. It’s one of many interventions that “stand to improve the health and well-being of older adults with disabilities and prevent adverse consequences due to unmet care needs,” she said.

| Adverse Consequences | Participation Restrictions | Lower Subjective Well-Being | |

| (Going without hot meals or showering or being unable to get out of bed or move around at home because no one is there to help them.) | (Being unable to visit friends and family or attend religious services or other events due to health conditions or physical limitations.) | (Experiencing more frequent negative emotions such as sadness, boredom, or dissatisfaction with life.) | |

| Social and Economic Environment | |||

| Higher neighborhood poverty | |||

| Higher neighborhood unemployment | |||

| Higher neighborhood public assistance use | |||

| Lower neighborhood social cohesion* | |||

| Health Care and Social Service Delivery | |||

| Lower Medicaid HCBS generosity* | |||

| No presence of state MLTSS* | |||

| Lower state minimum wage | |||

| State Medicare Advantage penetration | |||

| State percentage of Medicaid-enrolled residents | |||

| No state paid family leave | |||

| No state paid sick leave | |||

| State Unemployment Insurance Modernization Act* | |||

| State No Wrong Door score* | |||

| Lower direct care hourly wages | |||

| Lower Medicare reimbursement | |||

| Built and natural physical environment | |||

| Presence of state coordinating council* | |||

| No state web accessibility laws | |||

| Lower neighborhood broadband access | |||

| Lower neighborhood household-to-income ratio | |||

| Younger neighborhood housing age | |||

| Any housing quality issues | |||

| Residing in homes or apartments in the community (compared to residential care) | |||

Source: Chanee Fabuis et al., “The Role of Person- and Family-Oriented Long-Term Services and Supports,” Milbank Quarterly 101, no. 4 (2023): 1076–1138. https://doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12664.

Definitions

Neighborhood cohesion: a measure reflecting how well people in a neighborhood know each other, are willing to help each other, and can be trusted.

HCBS generosity: share of states’ Medicaid long-term services and supports (LTSS) expenditures that are allocated to home- and community-based supports.

MLTTS: Managed long-term services and supports.

Medicare Advantage penetration: percentage of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage by state.

State Unemployment Insurance Modernization Act: offers unemployment insurance benefits to individuals who lost or left jobs due to family member’s illness or disability and are ready and able to begin working again.

State No Wrong Door score: approach enables individuals and families to access public and private services regardless of which organization or government agency they contact.

State Coordinating Council: addressing transportation needs of the elderly, disabled, and those needing affordable and accessible transportation to get to work, job training, and education programs.

Laura Bailey of the University of Michigan contributed to this report.