Elizabeth Lawrence

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

August 26, 2022

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Children and youth living in the United States are dying at higher rates than their peers in other high-income countries. Where I live, in Las Vegas, the violence in local schools has made national news. The mental health crisis among children and teenagers described in detail in newspapers and the new Ken Burns PBS documentary is real. And we need to address it.

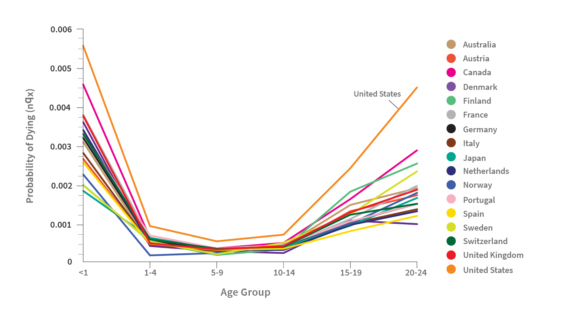

The mental health crisis is evident when we look at national death rates. American children and youth are dying from preventable causes, as my coauthors and I show in the “Dying Young” Population Bulletin. Car crashes, firearm accidents, homicides, and suicides are not genetic, biological, or natural, but are the product of our social organization and societal values. The large, consistent, and growing divergence between the United States and other high-income countries suggests that we are not marshalling resources to address this urgent problem or, at least, we are not marshalling them effectively. (See figure.)

Notes: Data for Germany are for 2017.

Source: University of California, Berkeley (USA) and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany), Human Mortality Database, data downloaded Aug. 16, 2021.

Mental health lies beneath much of the violence, drug use, and suicides taking the lives U.S. children and adolescents. In past decades, we may have worried about teenage pregnancy, alcohol use, and college enrollment, but rates of teenage pregnancy and use of alcohol and tobacco have generally gone down while college enrollment has gone up. Today, firearms, potent drugs, and mental health problems are the biggest concerns for youth’s well-being. Firearm injuries are the leading cause of death among U.S. youth, surpassing car crashes. Overdose deaths among adolescents have risen due to the extreme risks from fentanyl and other synthetic drugs. Teenagers today spend less time going out with their friends or playing youth sports. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of teenagers reporting anxiety or depression was on the rise.

It would be easy if there was one cause to all of this suffering. Exasperated, we point fingers at school policies, social media, and pandemic closures, but none of that finger-pointing leads to change. In contrast, a solution-oriented approach identifies concrete improvements that foster safe and healthy environments for children to grow physically, socially, and emotionally. We need to enact downstream measures that directly affect the physical and mental well-being of our youth. In the “Dying Young” Population Bulletin, my coauthors and I highlight some recommendations, such as universal background checks for firearms, which already have broad public support and need legislative action.

We should also look upstream to consider the underlying social structures that affect children’s health and safety, making multiple causes of death and many other hardships more common among U.S. children and youth than those in other wealthy countries. One important goal will be reducing child poverty, which affects nearly one in five U.S. children and has long-lasting effects on health and development. Eliminating child poverty is an achievable goal, and we can start with the policies and programs that rigorous research has shown to be effective.

These problems are not easy ones to fix and will require constructive, thoughtful, and practical actions. Families, schools, neighborhoods, cities and counties, states, and country are all powerful influences on the lives and well-being of children and youth. Solutions must consider not only how to improve each of these contexts, but also how these contexts are interconnected.

Families cannot thrive without supportive schools, and schools cannot succeed without sufficient local or state resources. In the “Dying Young” Bulletin, we conclude: “More purposefully supporting infants, children, young adults, and young families is an essential way to ensure a brighter future for all Americans.”

As the trends and patterns documented in the Bulletin have continued and worsened, the call to action has become more urgent: We need to act now to preserve the health and safety of the youngest Americans.