John Haaga

Former Director of Domestic Programs

August 28, 2024

Former Director of Domestic Programs

This is the second blog in a series on the 100th anniversary of the 1924 Immigration Act, the most restrictive in the nation’s history. Read the first here.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme,” goes a saying attributed to many notable figures, including Mark Twain. The same could be said of U.S. immigration policy, where many of the same themes have persisted over the last century. What has changed is how many people are coming to the United States, where they’re coming from, and how people feel about it.

The United States is often called “a nation of immigrants,” but for at least the last 100 years it could also be called “a nation that tries to limit immigration.” In modern times, the United States has never had a simple open borders policy, nor in practice has it ever been able to stop unauthorized immigration.1 To set current debates in context—and to gain appreciation for the complexities—it’s useful to look back at the history of U.S. immigration policy.

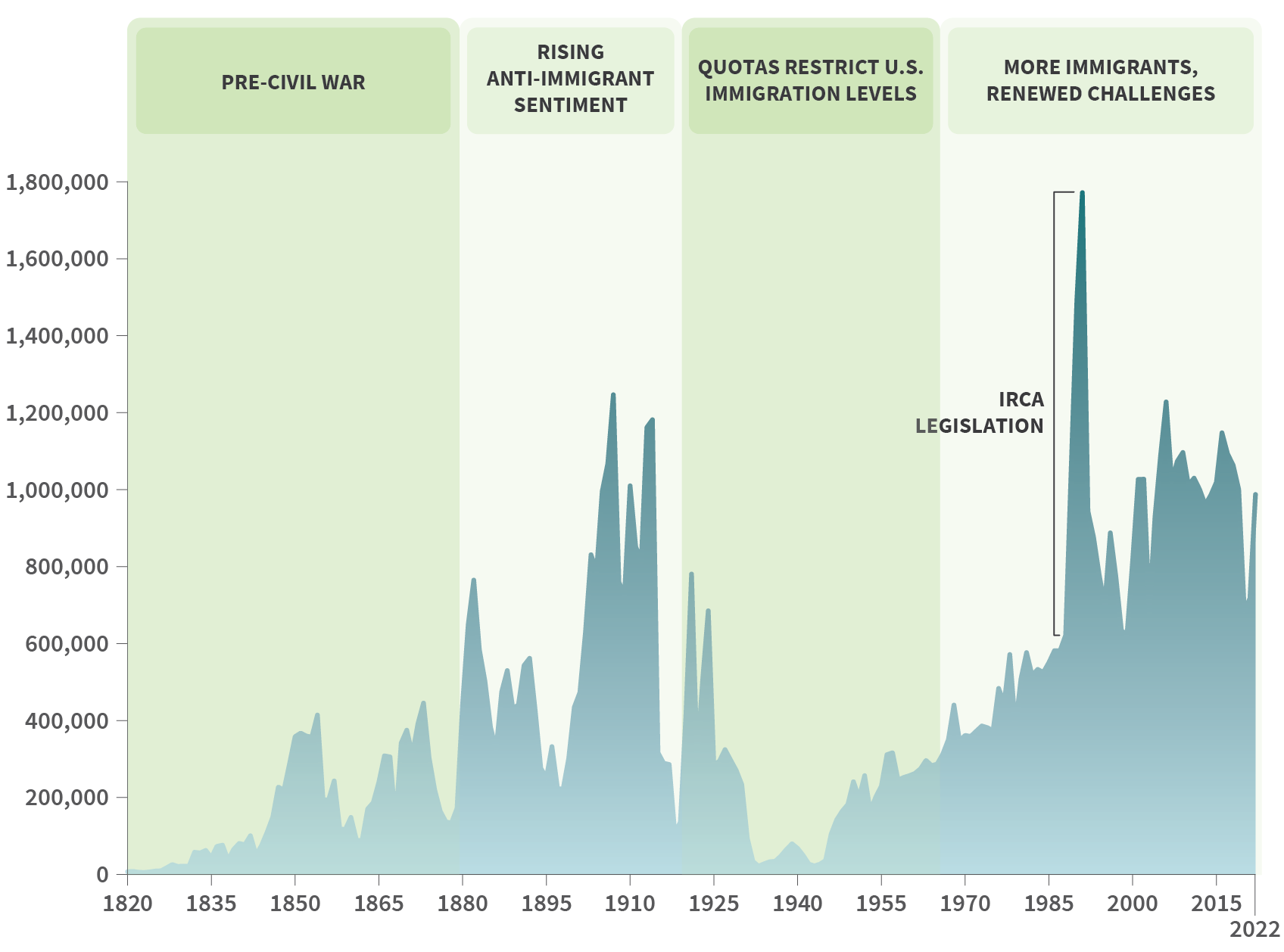

Note: IRCA legislation refers to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, which provided a path to legal residence for millions of unauthorized immigrants.

Source: PRB analysis of data from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Homeland Security Statistics, “Table 1: Persons Obtaining Lawful Permanent Resident Status: Fiscal Years 1820 to 2022,” Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2022.

The Founding Fathers did not have much to say about immigration policy. The Declaration of Independence showed a preference for unimpeded immigration, as one of the prominent charges against King George III was that he “has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States, for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither…” The Constitution (Article 1, section 8) granted Congress the power to “establish an uniform Rule of Naturalization…” but said nothing about what that rule should be.

Voluntary migration (as opposed to forced migration due to slavery) was not much of a political issue until the 1840s, when a surge of migration from Ireland, German lands, and other parts of Europe beset by famine and revolution led to a nativist reaction, often violent.2 A new U.S. political party, the Native American Party (popularly called the “Know Nothings”), rose to prominence in the 1840s and 1850s, before immigration lost salience to the issues of slavery and secession.3

After the Civil War, large-scale immigration from Europe resumed. Asian immigrants also came to the United States to work in mines and on the railroads, farms, ranches, and orchards of the rapidly developing West. Racism and concern about competition from low-wage workers spurred the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which limited the number of Chinese immigrants and denied U.S. citizenship to those born in China. Later laws barred Chinese immigrants from coming to the United States altogether.4

Concerns about Japanese immigration and local and state measures against the new immigrants and their families led to a 1907 “Gentleman’s Agreement” between the United States and Japan. Under this agreement, never formalized as a treaty, the Japanese government would not allow further emigration of laborers to the United States, and the U.S. government prevented migration of Japanese laborers from Hawaii (then a territory) to the U.S. mainland.5

Immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, 1920.

Photo credit: Bain News Service via the Library of Congress.

A new wave of immigration from Eastern and Southeastern Europe drew national attention as large numbers of Jews fled violence and persecution in the territories of the old Russian Empire. Racism and antisemitism fueled pseudo-scientific theories of eugenics, which were used to discriminate against all but Northern and Western Europeans. Labor leaders’ fears of a postwar recession also led to concerns about competition for jobs from new immigrants—a recurring theme in immigration policy debates.6

When the United States entered the First World War in 1917, Congress passed a law requiring literacy in adult immigrants and barring immigration from most of Asia. At the war’s end, most Americans wanted a return to “normalcy”—as President Harding termed it—but revolutions abroad, terrorist bombings and a subsequent violent crackdown by federal agencies, and widespread racial violence all stoked fears, much of it directed at immigrants.

For the first time, the 1921 Quota Act set limits on the overall numbers of immigrants, capping the maximum at 3% of the foreign-born population as counted by the 1910 Census and imposing quotas for each sending nation proportional to their share of the population in that Census.

The 1924 Immigration Act made these quotas permanent, setting annual limits at 2% of the foreign-born population from each country as of the 1890 Census, thus moving the baseline back to the period before the largest wave of immigrants arrived from Southern and Eastern Europe. Immigration from Japan, except for a few students and professionals, was banned altogether.7 This unilateral abrogation of the Gentleman’s Agreement infuriated the Japanese (recent allies of the United States in World War I) and exacerbated a deterioration in relations between the two countries.8

The 1924 Act was seen at the time as a fundamental break with the past. A 1925 essay in the Atlantic Monthly noted that “The United States is the first example of a great nation adopting a general programme [sic] of restriction against aliens of all kinds in order to carry out a far-reaching national, racial, and economic policy.”9

The 1924 Act did not impose national quotas on immigration from Mexico and other Western hemisphere countries. Attempts to limit Mexican migration had been defeated by members of Congress from Western States, representing the interests of mine and railroad owners, ranchers, farmers, and those developing large irrigation projects, who relied on an uninterrupted flow of workers from Mexico.10 Uneven enforcement of visa requirements created legal uncertainty for Mexican immigrants and even native-born Mexican Americans in the 1930s. The U.S. Border Patrol (established in 1924) and local law enforcement agencies conducted raids in the Southwest, and hundreds of thousands of people were deported, most often without a formal administrative or judicial procedure.11

Between 1924 and 1965, the quotas remained in place. With minor exceptions, unused slots under the cap for one country of origin could not be reallocated to another. There were years in the 1930s when net migration to the United States was less than zero, with more people leaving the country then entering.12

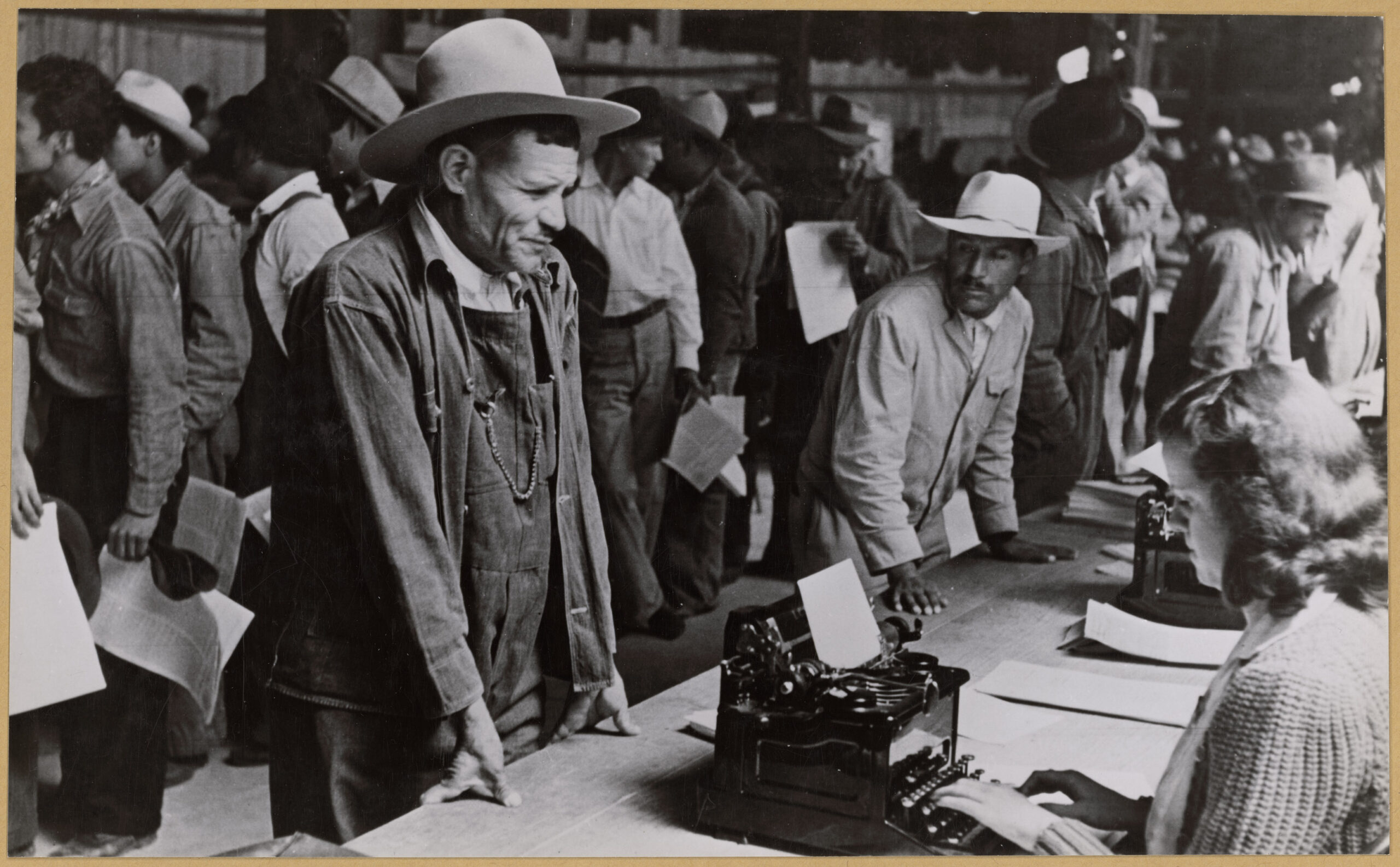

Many who supported the restrictions sought to keep demand for native-born workers, and their wages, high.13 But pressure also grew from employers, especially in the West, who faced shortages of laborers. During World War II, a formal agreement with the Mexican government established what was known informally as the Bracero Program, which

recruited and registered temporary workers, unaccompanied by families, provided they received transportation to the work site, and adequate wages and working conditions. Hundreds of thousands of Mexicans replaced workers who had gone off to the war. The program was viewed as a success, at least by U.S. employers, with some of its principles carried over into more recent temporary visa provisions for agricultural and other specialty workers.14

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 ushered in a new era of increased immigration, removing the national quotas and prioritizing family reunification in admission decisions. Since 1965, the largest category of legal immigrants has been immediate family members of U.S. citizens.

Despite attempts to regularize labor migration, unauthorized immigration persisted and even increased after the 1965 Act, during years of rapid population growth in Mexico. The Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 was intended to address unauthorized immigration by strengthening border security while allowing undocumented immigrants living in the United States to apply for legal status. The act contained three major provisions, designed as a compromise among competing interests:

IRCA also recognized that states, local governments, and school districts bore the immediate cost burden of providing services such as education and health care to newly legalized immigrants. Meanwhile, the federal government derived most of the fiscal benefit of the payroll and income taxes immigrants paid. In response, the federal government developed a system to provide impact aid to states and localities.15

IRCA was only a partial success. The legalization program achieved its goal of providing a path to permanent resident status and eventually citizenship for unauthorized migrants who had lived more than a decade in the United States, with some 3 million applying and more than 2.5 million becoming legal permanent residents under IRCA.16 And while unauthorized migration appeared to decline for a few years, it picked up again during the economic boom of the 1990s. Employer sanctions proved difficult because insufficient resources were devoted to enforcement, in part because it was unpopular. Since the 1980s, U.S. citizens have appeared to be more willing to have immigration laws enforced at border states than to have federal agents conducting raids at meatpacking plants, construction sites, or hospitality venues that employ unauthorized immigrants.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Immigration and Nationality Act as Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Lady Bird Johnson, Muriel Humphrey, Sen. Edward (Ted) Kennedy, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, and others look on.

Photo credit: LBJ Library photo by Yoichi Okamoto.

The 1990 Immigration Act was intended as a follow-on to IRCA. It restored an overall ceiling for legal immigration, though still with a major exception for immediate family members of U.S. citizens. It also increased the proportion of immigrants admitted for employment-based reasons and gave preference to professionals and people with skills needed in the U.S. labor market. In addition, it created the lottery system for visas for countries that had not had many recent emigrants to the United States. These provisions were meant to rectify what were seen as imbalances created by the 1965 and 1986 acts, which had greatly favored family reunification and workers with less education.17

Mexican farm workers who have been accepted for farm labor in the U.S. through the Braceros program.

Photo credit: National Archives.

The 1924, 1965, 1986, and 1990 Immigration Acts all dealt comprehensively with immigration from all parts of the world, whatever the migrants’ motives for wanting to come to the United States. But there has also been a more targeted stream of policy measures to deal with refugees from political violence and persecution.

Before World War II, there was no specific provision for humanitarian admissions; European Jews desperately trying to flee the impending Nazi genocide were turned away once the annual quotas for their countries of origin were filled. After the war, the sheer number of displaced people with no reasonable hope of going back to their homes led to new calls for special consideration for refugees. Lacking new legislation by Congress, Presidents Truman and Eisenhower acted on their own authority to admit refugees during crises under so-called “parole” authority, including Hungarian refugees after the brutal suppression by the Soviet army of a revolt in 1956 and Cubans after Fidel Castro’s takeover in 1959 and the Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1962. Congress acted to make refugee policy more systematic following the collapse of the Republic of Vietnam in 1975 and subsequent displacements caused by continued war and repression throughout Indochina.18

There is a good deal of international cooperation in managing the flow of refugees—for example, many refugees admitted to the United States have first been certified and housed by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, and the United States has an annual quota for refugee resettlement announced by the president in consultation with Congress. In contrast, the process for those who claim asylum at the border or inside the United States is less manageable. Adjudicating an asylum claim while respecting due process has often proved difficult, especially when an understaffed system is overwhelmed by a large influx of people seeking help.19 In the early 1990s, political violence in Haiti caused many would-be migrants to set out in boats for the United States. The U.S. Coast Guard intercepted most and diverted them to the naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where most had to wait months and years to have their asylum claims processed.

In recent years, the backlog is due to people seeking help at the southern border, typically from Central American countries but sometimes from Asia or Africa. Unresolved issues include how to process claims quickly and fairly, and where to house claimants and their families in the meantime. Many advocates seek a greater focus on humane treatment of asylees awaiting a decision; but others are more concerned with deterring further arrivals, securing the borders, and preventing unauthorized immigrants from taking up residency in the United States.

Policy toward refugees and persons claiming asylum has always been mixed, with more generous treatment of those fleeing regimes opposed to the United States, and less generous treatment of those fleeing civil wars, or gang violence. For example, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, hundreds of thousands of refugees from Ukraine have arrived by air and been rapidly resettled all over the country.

There is not yet a well-planned and adequately funded and staffed system for processing claims for asylum quickly and fairly, nor agreement on where and how to house claimants and their dependents while claims are processed. This suggests that we will continue to have more “repeats” and “rhymes” in our complex U.S. immigration policy.

In the last three decades, Congress has made several attempts at crafting comprehensive legislation on immigration reform, but none have succeeded. One of the most thoughtful and promising efforts was the bipartisan Commission on Immigration Reform. Its report, issued in 1994, made recommendations concerning the full range of issues, including border enforcement, employer sanctions, immigrant eligibility for social services, deportation of criminal immigrants, and curtailing immigration by improving conditions in source countries, notably Central American nations.20 Immigration policies, like all policies, produce gains to some and losses to others. The Commission’s report and supporting reports from the National Academy of Sciences concluded that immigration in general produces economic and financial gains for the nation as a whole but called for policies to share the benefits with other workers who may be displaced by immigrants.21 They also showed the disproportionate costs that states pay to support education and other services, and the net benefits that the federal government receives in revenue from taxes.

Immigration policy in 2024 needs to cope with issues that have been with us in various guises for at least a century, including how to reconcile goals of family reunification, humane response to crises abroad, and needs of employers for workers with particular skills; how to share the short-term costs among levels of government and across states and cities; and how (and where) to enforce the law. Immigration policy debates have often been heated, but it has been possible in the past to achieve compromises that balance interests and accord with our shared values.