Sara Srygley

Research Associate

Official reports suggest that Africa was somehow spared from the worst effects of COVID-19, despite warnings that the pandemic would be devastating for the continent. But researchers have uncovered a different picture of the pandemic’s impact in Africa.

Tara McKay and colleagues at Vanderbilt and American University report evidence showing that African countries experienced COVID-19 infections and deaths at levels similar to—and in some cases higher than—countries in other regions across the globe.1

“Although we may never know the full extent of COVID-19 infection and mortality on the African continent, the impact of the pandemic is very certainly greater than official data suggest,” said McKay.

African countries consistently reported lower rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths between 2020 and 2022 than countries elsewhere, despite fewer resources to tackle a widespread pandemic. One factor contributing to this so-called “Africa paradox” has been the challenge in gathering accurate data, McKay and team said.

Even before the pandemic disrupted the public health systems that track illness and mortality patterns, African countries varied considerably in reliably measuring and reporting deaths from all causes. During the pandemic, this variability—coupled with limited COVID-19 testing—led to inaccurate case fatality rates (CFR), infection fatality rates (IFR), and excess death measurements across the continent, the researchers found.

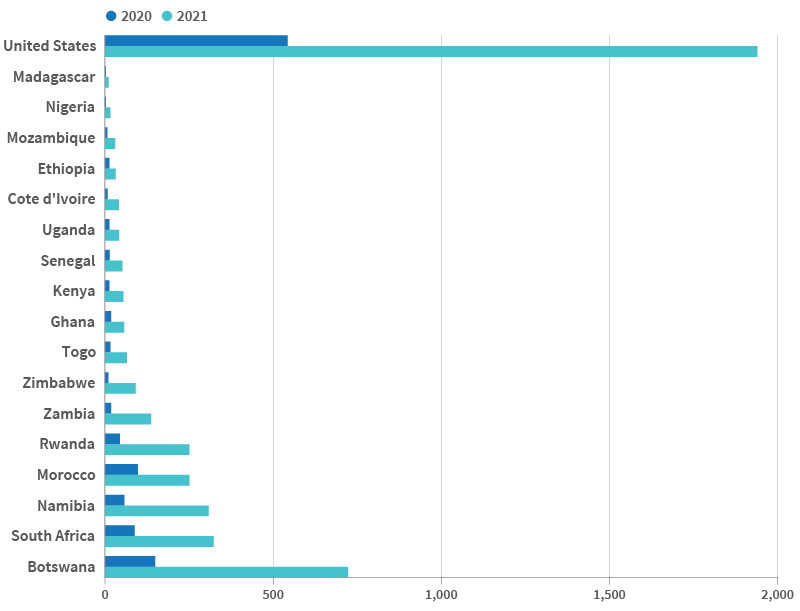

Testing capacity was a major issue for most countries during the early stages of the pandemic, but even after tests became widely available in high-income countries, access in the African region remained limited. By the end of 2021, 15 out of 23 African countries with COVID-19 testing data still tested fewer than 100 people per 1,000 population (see figure). Among countries with available data, testing rates ranged dramatically; for instance, while Botswana tested 723 people per 1,000 population, Madagascar tested just 11 per 1,000. By comparison, the United States had tested 1,940 people per 1,000 over the same period, meaning many people were tested more than once. Limited testing compromised the accuracy of case and infection fatality rates, as many cases and deaths went undetected.

Note: Note: Data are only displayed for African countries with data available for both quarters.

Source: Tara McKay et al., “The Missing Millions: Uncovering the Burden of Covid-19 Cases and Deaths in the African Region,” Population and Development Review 50, no. 1 (March 2024): 7-58.

Through a comprehensive review of available research and data on COVID-19 in the continent, including serological data, local data on morgue and burial site usage, CFR and IFR calculations, and excess death estimates, McKay and colleagues found compelling evidence that Africa’s case and death rates were higher, and more consistent with other parts of the world, than initially reported.

The serological data, which measure the prevalence of COVID-19 antibodies in the population, were particularly helpful because they provided a fuller picture of actual infection prevalence, including some asymptomatic infections or infections not captured by testing. These data show that the actual number of COVID-19 cases in Africa was much higher than reported; for example, comparing serological data to reported cases suggests that Kenya had detected only one out of every 415 cases in mid-2020.

Local morgue data also confirmed that a large share of COVID-19 cases and deaths had gone undetected. Research at the University Teaching Hospital in Zambia found that just 10% of positive cases detected among deceased persons in the hospital’s morgue were found prior to death. Most of the deceased had died in the community, and none had been tested while alive.

Burial site data revealed an increase in burials corresponding with the rising spread of COVID-19, challenging conventional methods of excess death measurement, which use public health mortality data such as vital records. In Ethiopia, a study from Addis Ababa University found a 30% increase in burial site registration in the third quarter of 2020.

Despite the overall debunking of the “Africa paradox,” COVID-19 transmission and spread in the continent was somewhat unique in the earliest phases of the pandemic. By the end of 2021, COVID-19 infection rates in Africa were widespread and in keeping with global trends. Yet, in mid- to late-2020, serological data revealed relatively low rates of infection, McKay and team reported.

Africa’s geographic and environmental conditions, including warmer weather and lower population density, may have played a small role in slowing the early spread of COVID-19. Researchers from Georgia State University and University of Dschang found that in 182 countries, urbanized areas were more likely to have higher COVID-19 case rates in the early part of the pandemic. Yet the study also found that the protection afforded by lower population density became less effective as the pandemic continued into 2021.

The responses of some African governments and communities also contributed to considerable variation in the spread of COVID-19 between nations, found a study out of Georgetown University. Countries including Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, and Uganda received praise for adapting previous outbreak response methods developed for the Ebola virus in 2014-2016 to quickly respond to COVID-19. While strong government responses in parts of the continent likely slowed early spread of the virus, many of these approaches were difficult to maintain, resulting in increased transmission by the end of 2021. Other countries, like Burundi and Tanzania, struggled to address the pandemic as leadership downplayed risks and limited public health responses, the study authors noted.

When looking at Africa’s health outcomes, it’s important to highlight the importance of strong government responses to the pandemic but also the limitations of those responses. Stay-at-home orders in sub-Saharan Africa led to a major loss of income for families, affecting food insecurity and other aspects of well-being, concluded a study out of Stellenbosch University. And social distancing requirements were unrealistic for many people in large cities, given the crowded living conditions and widespread use of public transportation.

“Ultimately, feel-good stories about specific countries take the focus away from inequality in deaths and the significant economic impacts of public health measures,” said McKay. “The false narrative of an Africa unscathed by the COVID-19 pandemic has likely limited demand, investment in, and timely delivery of vaccines to Africans, which has almost surely increased the burden of COVID-19 infections and deaths, given the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines at preventing severe disease and death.”

Without better COVID-19 data, countries may struggle to identify priority populations for vaccines and secure the donor assistance they need to save lives.

When the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020, few sub-Saharan African countries had reported a single case of the disease, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

In the United States, women from disadvantaged groups faced more barriers to contraceptive care during COVID.