Cathryn Streifel

Senior Program Director

This International Women’s Day, we’re looking at the impact of unpaid care work on women and girls and the global economy—and how PRB and CREG are helping address this urgent issue.

Caring for children and grandparents, cooking, cleaning, gathering water: Care work is essential for human well-being, for societies to function, and for sustainable economic growth. But around the world, a lack of public investment in care services and infrastructure has required individuals—principally women and girls—to fill the gap by performing unpaid care work1, a reality that keeps many out of school and the formal workforce.

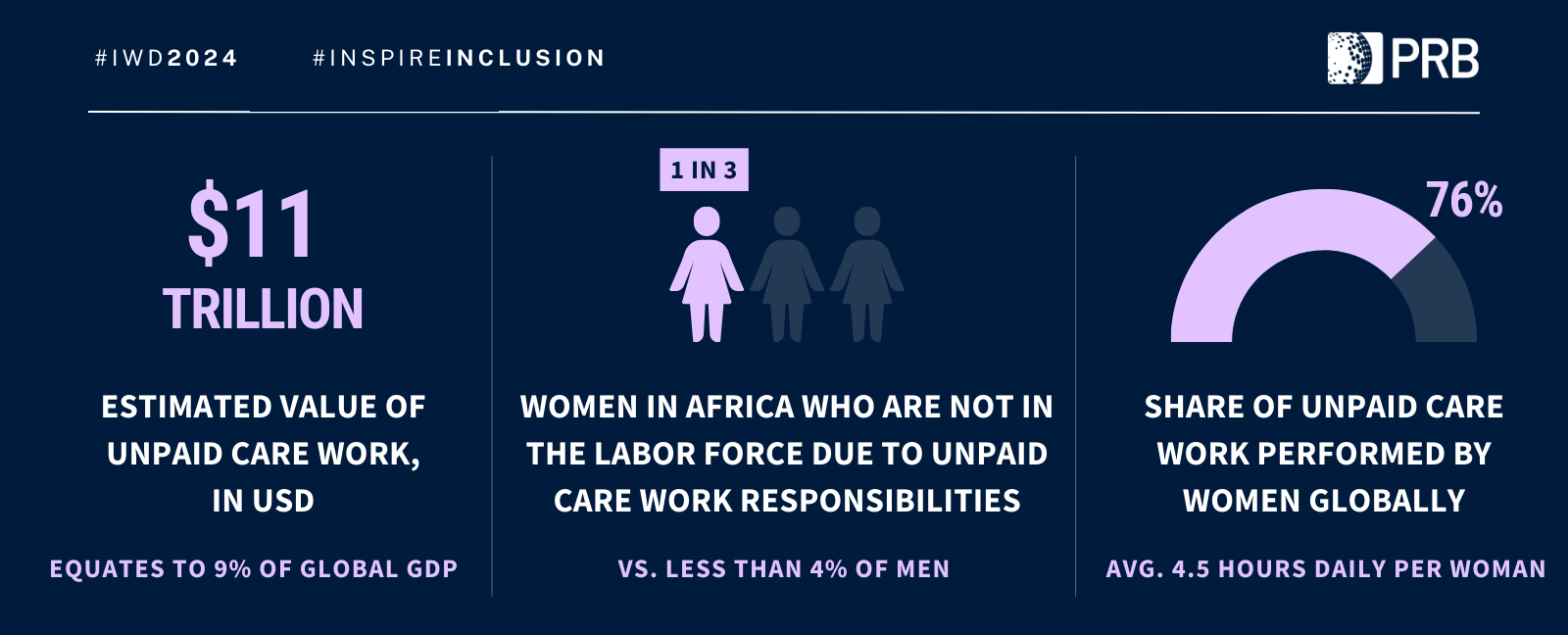

Despite its enormous value—$11 trillion, according to an estimate by the International Labour Organization (ILO)—unpaid care work has remained largely invisible in economic calculations, official statistics, and political discourse. And due to demographic and environmental trends, the demand for care work is projected to increase. Unless care policies and services are put in place, gender inequality and deficits in care will grow.

This International Women’s Day, we’re looking at the impact of unpaid care work on women and girls and the global economy—and how PRB and the Regional Consortium for Research in Generational Economics (CREG), based in Thiès, Senegal, are helping address this urgent issue in Francophone West Africa.

Globally, 16.4 billion hours per day are spent on unpaid care work, the equivalent of 2 billion people working full time without pay. Women perform 76.2% of this work, dedicating an average of four hours and 25 minutes to it each day.

In Africa, women ages 15 and older spend on average 3.4 times more time providing unpaid care than men. In Burkina Faso, a whopping 93% of unpaid care work is performed by women, which would amount to 29.9% of GDP were it paid, according to CREG’s estimates. Women and girls living in poverty spend significantly more time on unpaid care work than those with more wealth.

While unpaid care work is enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals, it has historically gone unmeasured in official statistics. One mechanism for capturing this work is time-use surveys, in which respondents report their hours spent in paid work, child care, socializing, volunteering, and other daily activities over a period of time. But due to the cost and complexity of administering these surveys, data on unpaid care work—despite being in high demand—are collected infrequently or not at all. (To date, only four Francophone West African countries have conducted time-use surveys.)

Unpaid care work limits the time caregivers—mostly girls and women—have available for education, employment, political engagement, and leisure, reinforcing gender inequality. More girls than boys drop out of secondary school due to the social expectation to perform household work, and girls who do more unpaid care work have lower rates of school attendance than other girls. Globally, unpaid care work is the principal reason women of working age give for not holding a paid job. In 2018, 606 million women of working age were outside the labor force because of family responsibilities, compared to only 41 million men. In Africa, 34.4% of women reported being outside the labor force due to unpaid care work, versus just 3.9% of men. Keeping women and girls out of the formal workforce makes them more likely to experience poverty, preventing them from contributing to social security and accumulating wealth, Oxfam reports.

Fueled by population aging and climate change, the demand for care work is increasing. In 2015, 2.1 billion people needed care, including 1.9 billion children and 200 million older persons, according to the ILO. By 2030, this number is predicted to increase by 200 million, including 100 million additional older persons. Meeting this demand will likely push more families—and particularly women and girls—into poverty.

In addition, the growing impacts of climate change will only make care work harder to provide—and more valuable. For example, water scarcity might force people to travel greater distances to collect water, increasing the time they must spend on this task. (Women and girls are responsible for collecting water in seven out of ten households without water on premises.) Additionally, by impacting people’s health—especially that of children, people with chronic illnesses, and older persons—climate change will increase the demand for care work.

Since 2019, PRB and CREG have partnered to support countries working to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal around care work, as part of the Counting Women’s Work Africa project funded by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Our organizations bring complementary expertise to the project, including CREG’s skills measuring the impact of demographic dynamics on economic growth and gender and PRB’s skills supporting the use of data for evidence-based policymaking.

Since 2020, our efforts have focused on Francophone West Africa, a region with unique challenges that make the need to address care work particularly acute. While it is home to a fast-growing population of young people—who could potentially make great contributions to the global workforce —little planning has been done to prepare for population aging, and the subsequent strain on the care workforce. Unpaid care work is not a priority in policy discussions, and the topic suffers from insufficient data, weak or nonexistent policies and services, and few policy resources, especially ones in the French language.

To generate useful data, CREG helps African governments improve their analyses of the effects of population dynamics on national economies by using National Transfer Accounts and National Time Transfer Accounts tools, the latter of which include age- and gender-specific data on who produces and who consumes unpaid care work. Together, PRB and CREG are creating a policy communication guide with information and practical steps to help people discuss unpaid care work with policymakers, as well as a policy brief featuring policy recommendations. In addition, PRB led a training on using strategic, evidence-based communication for researchers, academics, and technicians working on various aspects of unpaid care work across the West Africa region. Each participant built a targeted communication approach—with specific audiences, messages, and recommendations—to better lead the conversation and elevate unpaid care work as a policy priority in their country; they also learned from the experiences of peers from other countries.

Last, to create a space for policy dialogue, PRB and CREG are convening a series of workshops in Benin, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo for four groups with a vested interested in care work—ministries, parliamentarians, media, and civil society—to talk about the importance of measuring and including unpaid care work in economic calculations to develop evidence-based care policies. These discussions among stakeholders with complementary functions are an important first step for building cross-sectoral, multi-stakeholder dialogue in the future.

Through this collective work, PRB and CREG are helping to lay a much-needed foundation for evidence-based care policies and services in Francophone West Africa.