Toshiko Kaneda

Technical Director, Demographic Research

Fact: To understand fertility, demographers look at three factors: preferences (the number of children people would ideally like to have), intentions (the number of children people realistically plan for, given their circumstances), and behaviors (the actual number of children people end up having). Even in low fertility countries, most people still want children—but preferences often exceed intentions, and intentions often exceed actual births.

Childbearing is reduced both by shifting priorities (valuing careers, leisure, and personal fulfillment over marriage and larger families) and by constraints such as high costs, work-family conflict, unequal gender roles, economic insecurity, delays in partnering, and changing cultural norms.

Unknown: What factors, if any, can narrow gaps across fertility preferences, intentions, and behaviors. These factors can help explain how people plan for families, but there are some limitations. This information is collected through surveys, which are subject to bias; for instance, we know that societal expectations can lead some people to report wanting children, even if they’re unsure or don’t plan to. Additionally, survey results provide a snapshot in time, but preferences and intentions about children can and do shift. For example, younger people often plan for more children but adjust their intentions as life circumstances change. This can contribute to confusion about how individual choices are connected to fertility rates.

Fact: Comprehensive global reviews find no strong evidence that infertility is increasing, so it cannot explain the widespread decline in fertility rates. Measuring infertility is challenging, as definitions and data vary across countries.

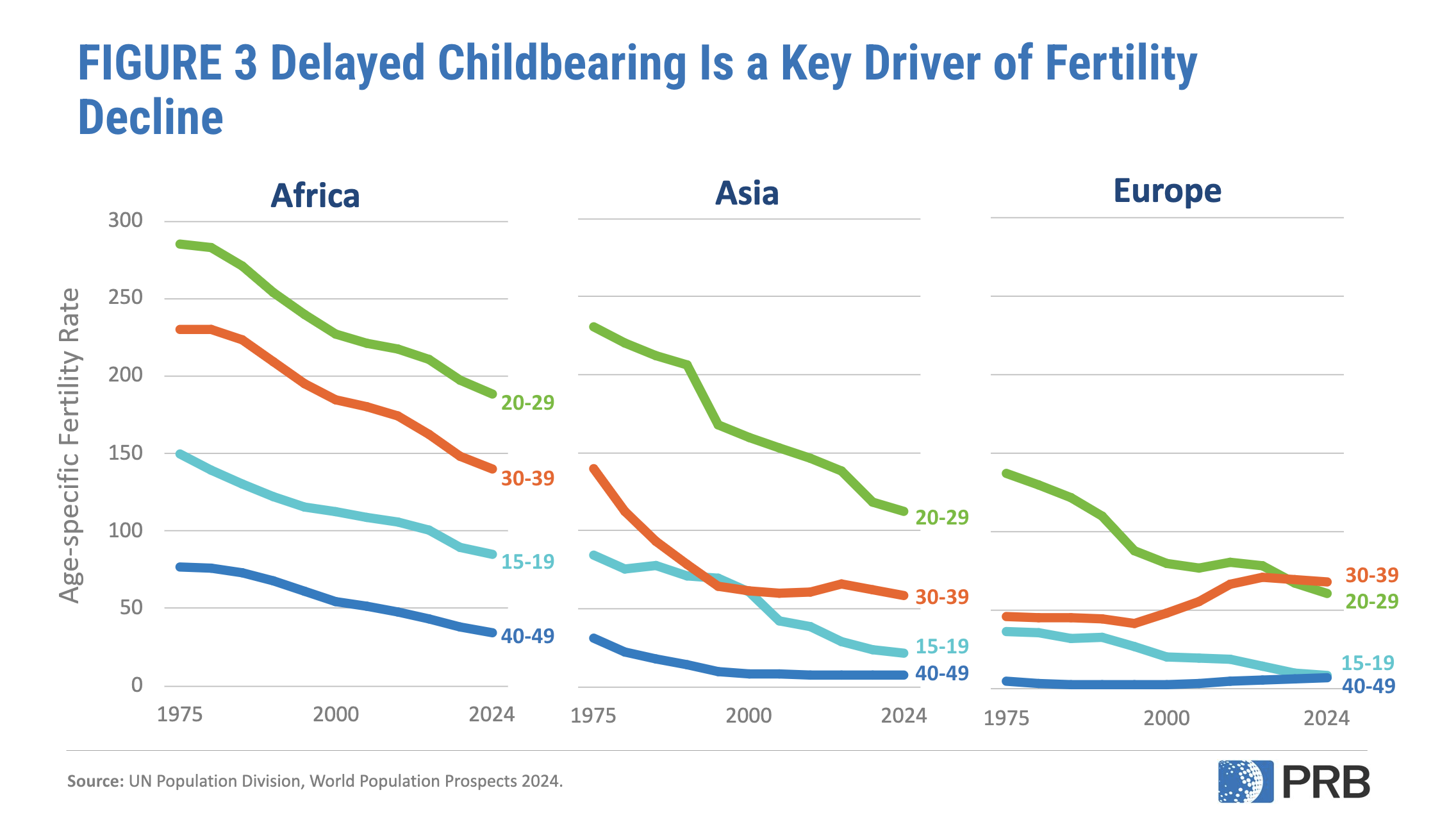

Worldwide, about one in six people experience infertility—not becoming pregnant after 12 months of unprotected sex—at some point in their lives. Rising childlessness is mostly shaped by social and economic factors, described above. Still, some trends, like having children later, can influence both infertility and fertility decline since delaying pregnancy shortens the reproductive window and biological ability to have a baby reduces as maternal age increases.

Unknown: Reliable infertility data are still limited in many countries, making it difficult to track trends or separate true biological infertility from voluntary delays and decisions to have fewer children. It also remains unclear how much lifestyle and environmental factors—such as stress, pollution, or obesity—might contribute to infertility trends.

Fact: Cash incentives and tax breaks given to parents tend to create only modest, short-term increases in births, often encouraging people to have children sooner, but with limited impact on overall births.

While such benefits can ease the financial burden of raising children in the short term, they typically make up only a small share of household income. It is possible that larger, long-term incentives could yield more births, but raising fertility to replacement levels this way would likely be prohibitively expensive.

Unknown: If financial incentives would have a stronger effect if paired with generous family support policies (see below).

Fact: Designed to make it easier for couples to work and raise children, these policies have only modest effects on fertility, often encouraging parents to have additional children but not people without children to enter parenthood.

However, such programs remain important for their other benefits, including reducing stress, improving well-being, and giving parents more options.

Unknown: Whether scaling up to universal, generous family supports could help close the gap between intended and actual births, or whether cultural and economic drivers will keep fertility low regardless. We also don’t know whether implementing such policies before the fertility rate declines below replacement level could help countries prevent or delay the decline to very low fertility; most countries with generous family supports only brought them on after fertility had already dropped.

Fact: Restrictive policies do not sustain higher fertility and come with serious health and human rights costs. Romania’s abortion ban in 1966 briefly doubled births, but fertility soon fell again while unsafe abortions, maternal deaths, and numbers of abandoned children soared.

Similarly, in the immediate aftermath of the 2022 Dobbs decision that overturned federal abortion protections in the U.S., states that enacted abortion bans saw a modest increase in births compared to projected trends (about 2–3% more than expected). However, total births continued to fall in most of states with bans, suggesting a temporarily slowing rather than a reversal. Limiting reproductive rights undermines health and freedom without addressing the real reasons families have fewer children.

Unknown: How far governments concerned about low fertility may go to restrict reproductive rights, and how such actions might backfire socially and politically.

Fact: Among high-income countries, those with lower gender equality (such as South Korea and Japan) tend to have lower fertility rates, while in those with higher gender equality—where caregiving and paid work are more equally shared—fertility tends to be somewhat higher.

Still, this pattern isn’t simple: We don’t know whether this relationship is causal, and some highly gender-equal countries (such as Norway and Sweden) also have very low fertility. In low-income countries with very high fertility, evidence does suggest that greater gender equality has contributed to fertility decline.

Unknown: Whether cultural norms will shift toward more equal sharing of work and caregiving, how meaningful those shifts might be, and whether they will raise fertility or primarily improve well-being (while fertility remains low).

Fact: Immigration can ease labor shortages and slow aging in the short to medium term. But immigration is rare (just 3-4% of the global population has migrated internationally) and as fertility falls worldwide, the global pool of young migrants will shrink, limiting immigration’s potential as a long-term solution.

Unknown: How much or where migration will actually flow in the future, and whether political and social systems will allow enough immigration to meaningfully ease pressures from aging.

Fact: Fertility decline leads to population aging—or, a growing share of older adults relative to younger people. At the family level, fewer children share the responsibility of supporting aging parents and grandparents, straining household finances. At the societal level, a shrinking pool of workers to retirees strains pension and health care systems and can slow economic growth. Population aging does strain retirement systems and shrink the workforce, but there is a lot societies can do to adapt.

Countries can experiment with a range of solutions such as adopting pension reform, raising the retirement age, getting more people into paid work, prioritizing immigration, and investing in productivity and innovation.

Unknown Whether these adaptations will be enough—since no society has ever faced aging on this scale and the pace of aging is rapid in low- and middle-income countries new to the trend.

Want to learn more about global fertility decline? Here we break down the key forces shaping global fertility patterns and what these shifts mean for families and societies, unpacking the demographic trends behind the assumptions discussed above.

Global fertility decline has been driven by lower child mortality, wider access to family planning, more education and jobs for women, and urbanization. The more recent decline to below-replacement and very low fertility levels reflects both economic challenges and broader social and cultural changes.

Rising costs, unstable jobs, delayed partnerships, and inflexible work environments make it harder to raise children, while greater emphasis on education, careers, and personal freedom has redefined ideas about family and what living a fulfilling life looks like (Figure 3). These factors explain why fertility is below replacement even where people still want children.

The total fertility rate is the average number of children a woman is expected to have over her lifetime if age-specific fertility trends prevail. It is a hypothetical measure based on current birth rate (importantly, it does not represent or predict the actual number of children women have). The replacement level fertility rate is the average number of children a woman needs to have for a population to replace itself from one generation to the next, assuming no migration and a natural sex ratio at birth (slightly more boys born than girls ). It is typically about 2.1 children per woman—two parents “replace” themselves with two children, plus an extra margin above zero because not all children survive to adulthood. However, even when fertility falls below 2.1 children per woman, population can continue to grow for several decades. That’s because many people are still in their childbearing years, so births remain high for decades, a pattern called population momentum.

The 2.1 figure can be a helpful benchmark for gauging whether populations might grow or shrink over time, even though actual replacement levels vary. But treating 2.1 as a “magic number” for stability is misleading: it ignores mortality and migration trends and says nothing about population momentum or population composition, such as age structure. Using 2.1 as a target fertility rate can also exacerbate fear about population decline and lead to policy solutions that focus only on raising birth rates. Such approaches can undermine reproductive rights, gender equality, and family well-being, while distracting from the rights-based priority of ensuring that people can have the number of children they want.

Population aging itself reflects progress: people living longer, healthier lives and women having more options and opportunities. Older adults are important contributors to societal and economic well-being, strengthening families and communities through caregiving, financial support, and volunteering. Many also remain in the labor force and could contribute even more with supportive policies. As societies adapt, population aging can also spur technological innovation, particularly in health care, assistive technologies, and automation, and even fuel a “silver economy” for goods and services for older adults. It also invites new thinking on gender roles, work-life balance, and more gender-equitable caregiving policies for both children and older adults.

Policymakers should focus first on helping women and families achieve the number of children they want. That means reducing the barriers between fertility preferences, intentions, and behaviors by investing in proven supports: affordable childcare, paid parental leave, flexible work arrangements, affordable housing, and gender equality in caregiving. These policies may not reverse fertility to “replacement level,” but they expand choices, improve well-being, and may close the gap between ideals and realities.

At the same time, evidence shows fertility is unlikely to return to past levels. Even if a country were to experience an unprecedented fertility rebound, it would take many decades to see the workforce or population grow again. Thus, societies must actively adapt rather than try to restore the past. Preparing for aging means strengthening pension and health systems, extending healthy working lives, investing in innovation and productivity, and expanding labor markets to engage groups typically underrepresented in paid work, including women, people with disabilities, older adults, and immigrants. Population aging is inevitable, but with adaptation, societal decline is not.

Too often, discussions about fertility decline center on the same tired question—“How do we get women to have more children?”—and end up with the same predictable answers. But there’s a much richer story to tell.

Around the world, new and overlooked ideas are emerging that can help families of all kinds thrive and help societies adapt to demographic change. Fresh angles to explore might include:

If you’re reporting on these issues, reach out—we’re here to help with data, context, and story ideas. To schedule an interview, please contact media@prb.org.