Kelvin Pollard

Former Senior Demographer

April 24, 2018

Former Senior Demographer

Senior Fellow

The Appalachian Region’s aging population may pose challenges “down the road” for local governments and community service providers, say the authors of a new Population Reference Bureau (PRB) report for the Appalachian Regional Commission. The Region’s share of residents ages 65 and older exceeds the national average, and Appalachia’s population in the prime working years (ages 25 to 64) declined between 2010 and 2016, while it grew nationally.

The Appalachian Region: A Data Overview From the 2012-2016 American Community Survey—coauthored by Kelvin Pollard, PRB senior demographer, and Linda A. Jacobsen, PRB vice president for U.S. Programs—examines trends and population characteristics at the regional, subregional, state, and county levels using recently released American Community Survey data and the Census Bureau’s latest population estimates.

The Region encompasses 205,000 square miles along the Appalachian Mountains from southern New York to northern Mississippi, including portions of 12 states and all of West Virginia.

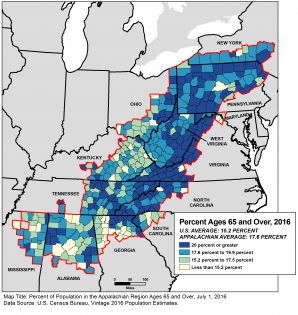

The report shows that the share of residents ages 65 and older (17.6 percent) in the Appalachian Region exceeded the national average (15.2 percent) by two percentage points in 2016. Older persons made up at least 20 percent of the population in 157 of 420 Appalachian counties, almost three-fourths of which were rural counties outside metropolitan areas. In contrast, most of the 40 Appalachian counties with older population shares below the national average contain either metropolitan areas or colleges and universities.

The overall share of Appalachian residents ages 65 and older exceeds the U.S. average, but varies by county.

The authors point out that as the large baby boom generation ages, the share of residents ages 65 and older will continue to increase in both Appalachia and the nation. Yet while both the young adult (ages 18 to 24) and working-age populations have increased nationally since 2010, Appalachia has lost people in these age groups. For example, the Region had 13.2 million residents ages 25 to 64 in 2016, down 1 percent from six years earlier.

“The shifting age distribution of the Region’s population means that fewer workers are supporting a growing older population, which can have implications for the local tax base and the demand for community services for the elderly,” says Jacobsen. “In addition, adults in their prime working years are the economic engine of a community.”

The report provides data on education and disability in the Region, key features of human capacity. It shows that while working-age adults in Appalachia are nearly as likely to have completed high school as Americans in general, they are significantly less likely to have completed at least four years of college.

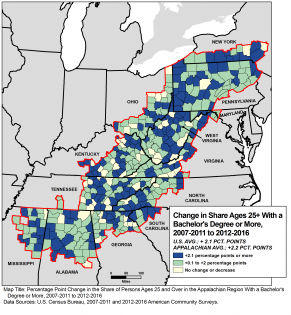

Since 2007-2011, the share of Appalachia’s working-age population with a bachelor’s degree or more has risen nearly two percentage points to just under 25 percent in 2012-2016. Room for further improvement remains, however, as the Region’s current prevalence is seven percentage points lower than the U.S. average of 32 percent. The authors call this “a striking indicator of the lower educational level of the Appalachian workforce,” and also point to variation within the Region. For example, they note that while less than 18 percent of working-age adults in Appalachian counties lying outside of metropolitan areas had bachelor’s degrees, the share in counties that are part of large metropolitan areas of at least 1 million was 33 percent—above the national average.

The share of Appalachian residents with a bachelor’s degree or more increased more than 2 percentage points between 2007-2011 and 2012-2016.

Disability rates in the Appalachian Region are higher than the national average. In the 2012-2016 period, approximately one in seven adults ages 18 to 64 in Appalachia reported a disability, compared with about one in 10 nationally, the report shows. (The ACS only includes disability data for civilians living outside of nursing homes and other institutions; it defines persons with a disability as having difficulty in at least one of the following six areas: hearing, vision, cognition, walking or climbing, self-care, or attending to the functions of independent living.)

Some parts of the Region have particularly high disability rates. In Central Appalachia, for example, more than one-fifth of working-age adults had a disability. Central Appalachia had 56 of the 101 Appalachian counties where the disability rate among 18- to 64-year-olds was 20 percent or higher.

“Central Appalachia’s historic reliance on mining and related resource-based industries, as well as Appalachia’s relatively high rates of cancer, heart disease, and diabetes, may be associated with the subregion’s high disability prevalence,” Pollard suggests. He also notes that among the 61 Appalachian counties where at least half of persons ages 65 and older had a disability, two-thirds were in Central Appalachia.

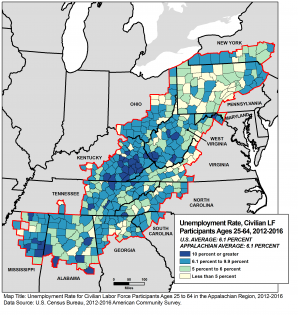

Appalachia’s unemployment rate matched the national average in 2012-2016, but great variation existed within the Region.

The full report includes detailed tables and county-level maps, covering state- and county-level data on population, age, race and ethnicity, housing occupancy and tenure, housing type, education, labor force and commuting, employment and unemployment, income and poverty, health insurance coverage, disability status, migration patterns, and veteran status.