Mark Mather

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

In the United States, over 24 million people provide unpaid care for older adults—a 32% increase from a decade ago

March 18, 2025

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Contributing Senior Writer

As the large Baby Boom generation enters advanced ages, more family members and other unpaid helpers are stepping in as caregivers. In just over a decade, the number of family caregivers regularly assisting older adults with daily activities at home grew by 32%, increasing from 18.2 million to 24.1 million between 2011 and 2022.1

While the caregiving cadre has grown, who’s getting care has also changed. Older Americans receiving family care are younger, better educated, and less likely to have dementia than they were in 2011, report Jennifer L. Wolff of Johns Hopkins University, independent consultant Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman of the University of Michigan.

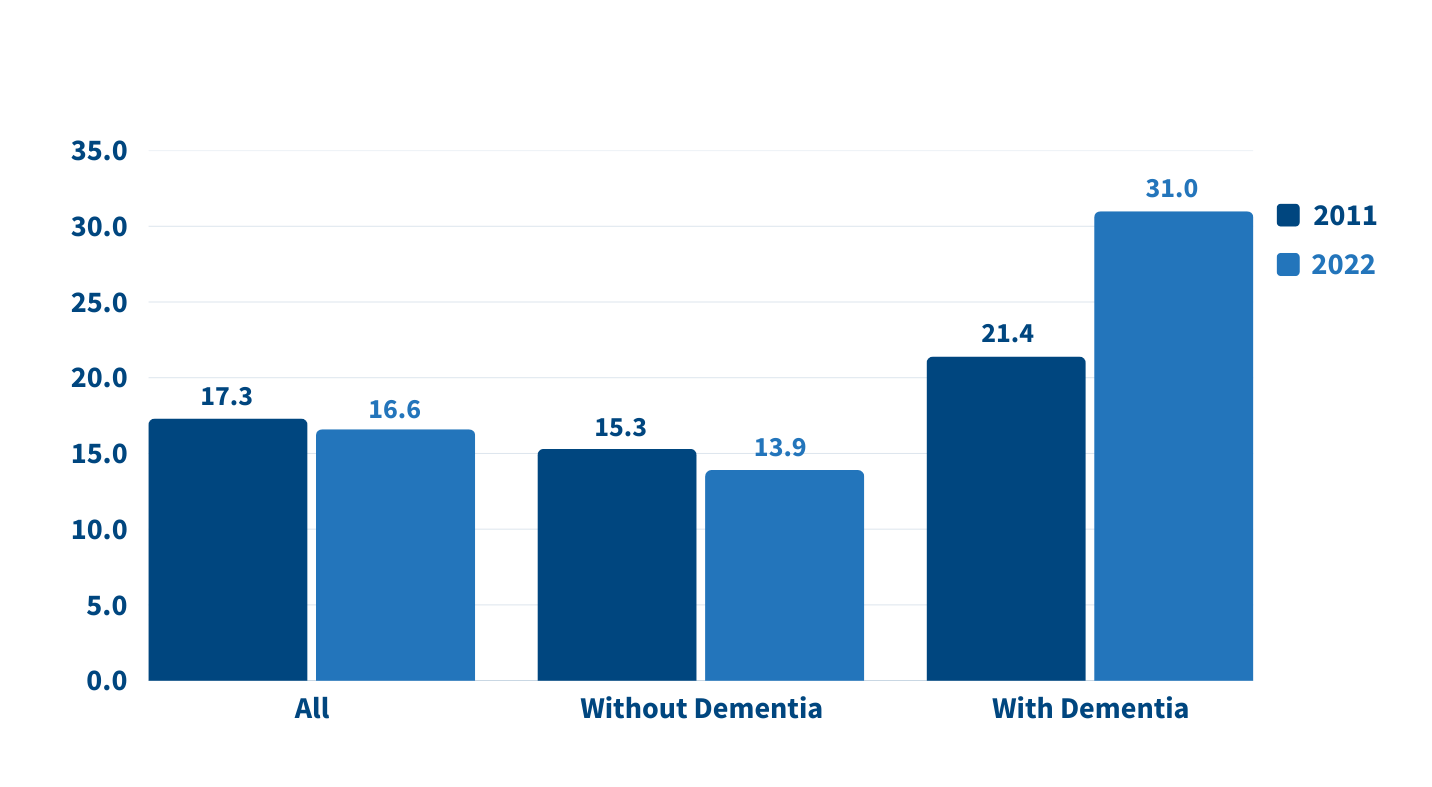

The increase in family caregiving partly reflects the rising share of older adults with multiple chronic conditions, such as heart disease, hypertension, stroke, and cancer. And while the share of older adults with dementia has declined, unpaid caregivers average twice as many hours each week caring for people with dementia than without dementia (about 31 hours versus 14), Wolff and team found (see Figure 1).

In addition, a new study estimates that the number of new dementia cases will double over the next 40 years as the population ages—setting the stage for more demands on dementia caregivers and more changes to the caregiving landscape.

“Understanding the changing composition and experiences of family caregiving has never been more important, but it is challenging to assess,” the researchers write. “[It] requires consistent measurement for well-characterized, generalizable samples of people who receive and provide help.”

The nationally representative National Study of Caregiving and the National Health and Aging Trends Study offer important insights. The two studies provide a snapshot of the family caregivers that help Americans ages 65+ who live in the community (i.e., at home or with a relative) or in a residential care setting other than a skilled nursing facility, such as an assisted or independent living facility, a personal care home, or a continuing care retirement community.

Family caregivers include relatives and unpaid helpers, like neighbors and friends, who assist with personal care tasks like bathing and dressing; mobility tasks like getting out of bed and getting around the house; and household activities such as laundry, food preparation, shopping, and managing money.

On average, the time that family caregivers spent helping older adults with dementia increased by almost 50% over the decade, rising from 21.4 hours per week in 2011 to 31.0 hours in 2022. By contrast, time spent assisting older adults without dementia fell from 15.3 hours a week in 2011 to 13.9 hours in 2022 (Figure 1).

Source: Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

People caring for older adults with dementia have high—and increasing—demands on their time. More than half (51.7%) of dementia caregivers lived with the person they were caring for in 2022, up from 39.4% in 2011, Wolff and team report. And the share able to hold jobs—outside their caregiving work—dropped from 42.5% to 34.6% during the same period.

Among caregivers with formal jobs, the share who reported challenges with their employment—including working fewer hours or being less productive—increased over the decade, regardless of whether they cared for someone for dementia.

“Challenges are exacerbated when caregivers are in poor health themselves; have a lack of choice in assuming the caregiving role; and, for the substantial proportion of family caregivers who are employed, work in low-wage jobs with limited flexibility,” the researchers note.

Which older Americans get family care? As in the past, they tend to be female, non-Hispanic white women who are married or widowed. But growing numbers of family care recipients are male and have some college education. More are also separated and divorced compared to 2011, reflecting national trends.

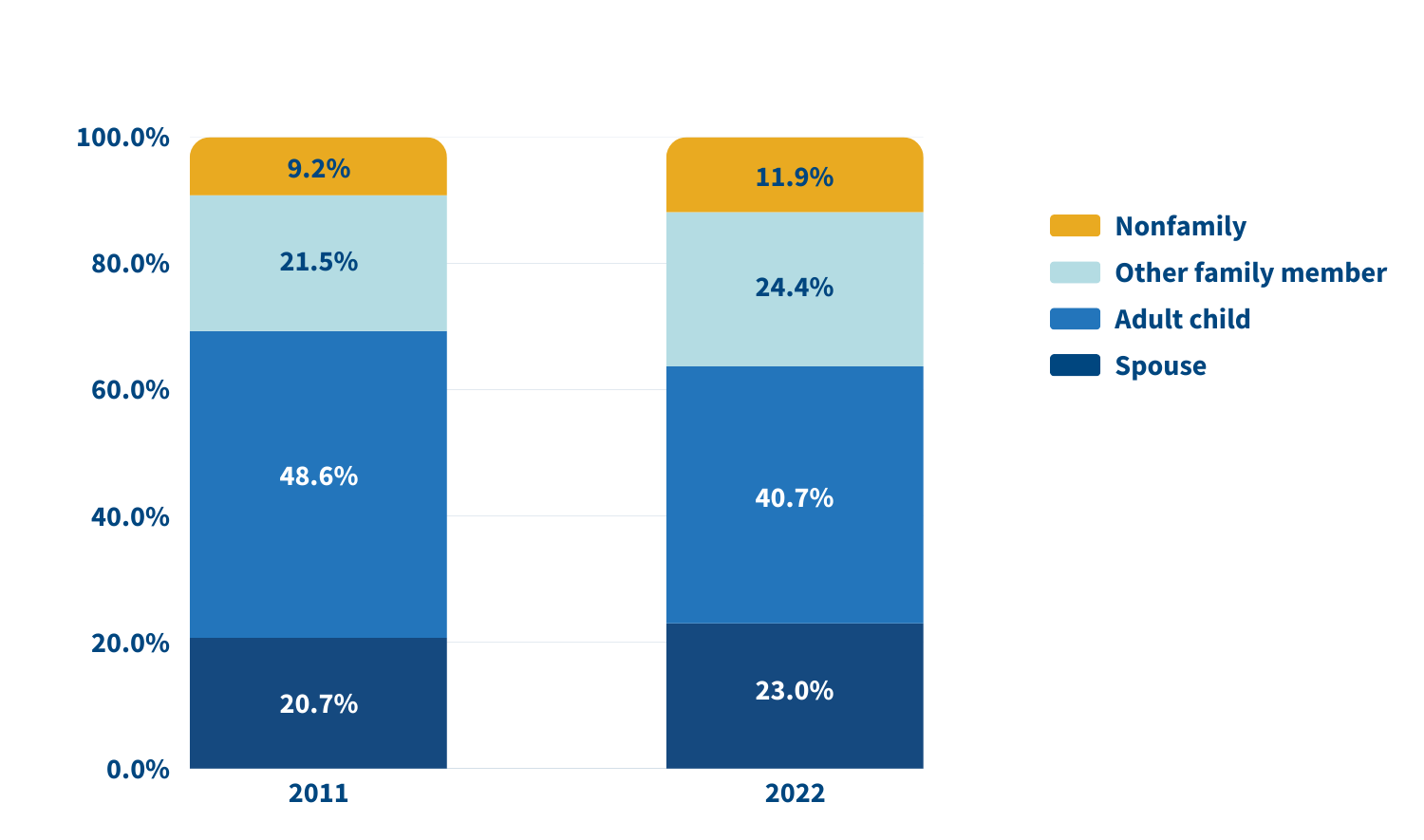

Who’s providing care? Family caregivers continue to be largely female and married, and most report being in good health. In 2022, adult children still made up the largest share of family caregivers for older adults, at 40.7%, but this represents a significant decline since 2011 (Figure 2).

Source: Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.

In 2022, adult children accounted for about half (49.1%) of family caregivers for older adults with dementia, compared with 38.4% of caregivers for those without dementia. Just 17.7% of family caregivers for older adults with dementia were spouses, compared with 24.5% of family caregivers for people without dementia.

A sizeable share of family caregivers (17.0%) had children under age 18 at home in 2022, and 6% to 13% viewed their care responsibilities for older adults as a source of financial, physical, or emotional difficulty.

Despite these challenges, the researchers report a decline in the use of support groups (4.1% to 2.5%) and respite services (12.9% to 9.3%) between 2011 and 2022.

Many caregivers face extraordinary demands and should be the focus of support services, Wolff and colleagues say. They single out those caring for older adults with dementia or nearing the end of life, as well as caregivers “from racial and ethnic minority groups who are more likely to assist people who have extensive care needs in circumstances that involve scare economic resources.”

Family care needs are likely to rise as the number of U.S. adults ages 85 and older is projected to triple by 2050. The researchers note that the number of family caregivers rose even as the long-term use of skilled nursing facilities among older Americans dropped and community living increased. The challenges these caregivers continue to face is “sobering,” they write, including competing time demands from work and child care while spending an average of 17 hours per week on care. In addition, about 1 in 8 family caregivers report financial, physical, or emotional difficulties related to their caregiving roles, percentages that were largely unchanged over the 11 years examined.

Policies and programs to help reduce the financial, physical, and emotional burden of caregiving exist, but do not represent a coherent strategy, the researchers say. “Local, state, and federal policies are a patchwork that is uneven in availability and largely symbolic in magnitude,” they argue. Addressing the needs of family caregivers will require a “cohesive framework in support of the care economy.”

1. Jennifer L. Wolff, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Vicki A. Freedman, “The Number of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million to 24 Million, 2011–22,” Health Affairs 44, no. 2 (2025): 189-95.