Mark Mather

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Dementia is one of the nation’s most expensive old-age health conditions and the most time consuming for family caregivers.

May 28, 2020

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Contributing Senior Writer

Dementia is one of the nation’s most expensive old-age health conditions and the most time consuming for family caregivers. As many as 6 million people ages 65 and older live with Alzheimer’s disease in the United States, representing about one in 10 older Americans.1

However, rates of dementia are not uniform across the older population. Those with lower levels of education, the oldest old (people ages 85 and older), women, and racial and ethnic minorities are at greater risk of dementia. The types of living arrangements of people with dementia—whether they live at home, in a residential care setting (such as assisted living), or a nursing facility—also differ depending on the availability of family caregivers and financial resources.

This issue of PRB’s Today’s Research on Aging (Issue 40) summarizes what we know about the characteristics of people with dementia and their caregiving and living arrangements based on studies funded by the National Institute on Aging. Understanding the characteristics of those with dementia can help lawmakers design policies that better meet the needs of this rapidly growing population and their families.

Many conditions and diseases can cause dementia—a set of symptoms that may include memory loss and difficulties with thinking, problem-solving, or language. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause, but dementia can also be caused by injuries from impaired blood supply to the brain, often after a stroke. Other types of dementia include Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal disorders.

Alzheimer’s disease and other related dementias are characterized by progressive cognitive decline that interferes with independent functioning. In the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS)—a nationally representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older—respondents are classified into three categories: those with no dementia, possible (or early stage) dementia, and probable dementia. Participants are classified as having probable dementia if a doctor has told the person that they have dementia or Alzheimer’s disease.

For respondents without a diagnosis, dementia status is determined through a test measuring cognitive functioning, including memory (word recall), orientation (such as knowing the date and year), and executive functioning (drawing a specific time on a clock). In addition, for respondents unable to self-report, proxy respondents (typically a family member) answer the AD8, a series of eight Yes/No questions about the respondent (problems with judgment, reduced interest in hobbies, repeats self, trouble using tools or appliances, forgets correct month/year, trouble handling finances, forgets appointments, daily problems with memory/thinking).2

Cut points (based on standard deviations from the mean) are then used to group study participants into different categories. In the 2011 NHATS, 11% of Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older were classified as having probable dementia (10% among the non-nursing home population).3

Clinical guidelines developed by the National Institutes of Health and the Alzheimer’s Association also define three stages of Alzheimer’s disease (the most common type of dementia):

People with advancing dementia (or moderately severe dementia) are more likely to have difficulty with one of three daily living activities (dressing, bathing, or using the toilet) and cognitive difficulties that make it more difficult to manage medications or finances, whereas people with advanced dementia have difficulty with all these functions and more.5

No cure for Alzheimer’s disease currently exists, and no treatments have been proven to prevent its onset or delay its progression, but researchers are studying ways to treat the disease and expand support for people with Alzheimer’s disease and their families.

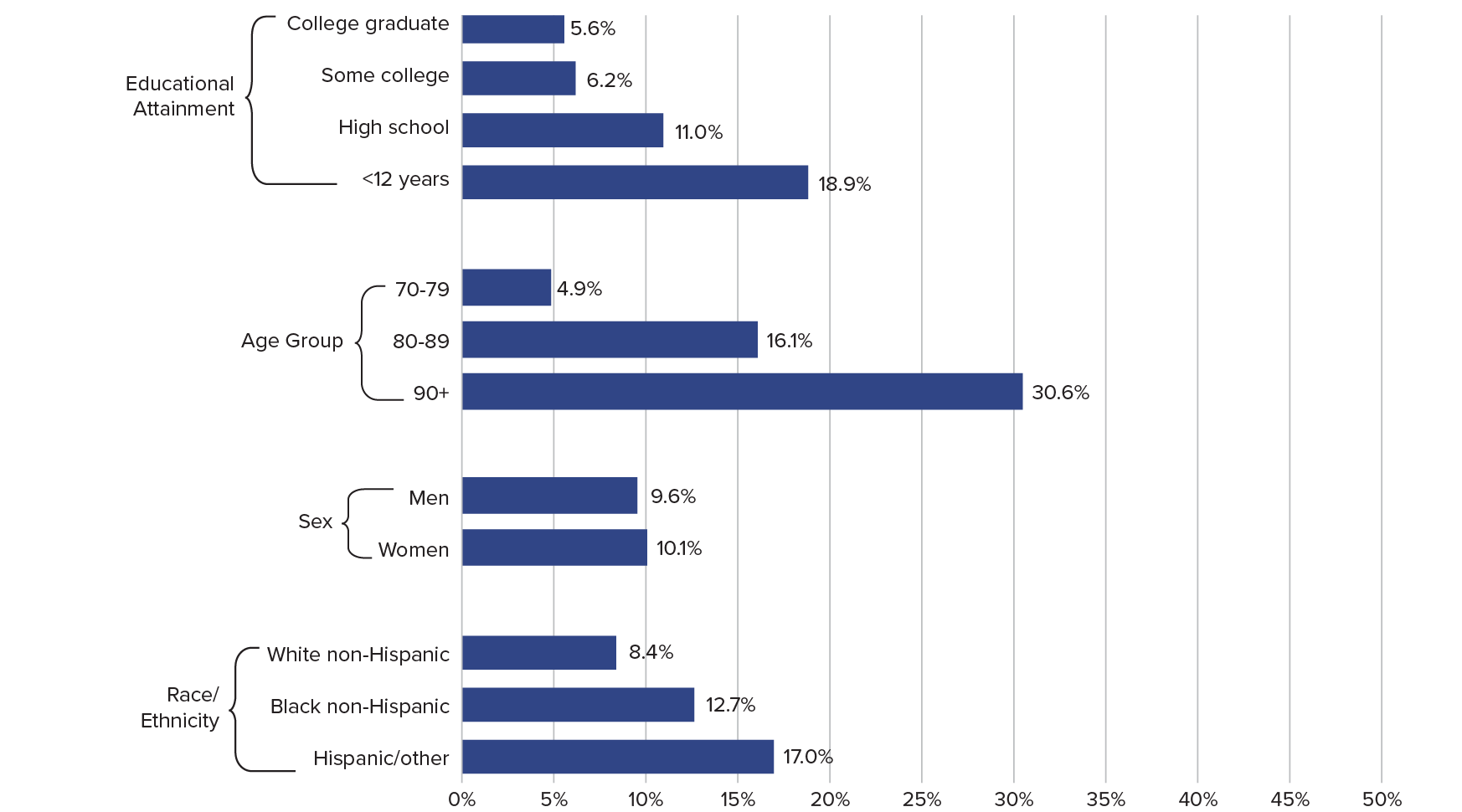

Higher educational attainment is associated with a lower risk for dementia. Older adults with more education have lower prevalence of dementia, more years of cognitively healthy life, and fewer years with dementia.6 In 2015, 6% of older college graduates (ages 70 and older) had probable dementia, compared with 19% of their counterparts with less than 12 years of education (see Figure 1).

Numerous studies have found that more schooling is associated with a lower risk of dementia. Researchers explain this connection in a variety of ways. They suggest that education may directly affect brain development by creating a cognitive reserve (stronger connections among brain cells) that older adults can draw upon if their memory or reasoning ability begins to decline. They also suspect that people with more education may be better able to develop techniques to compensate or adapt in the face of disrupted mental functions. In addition, education brings multiple advantages. They point out that people with more education tend to have healthier lifestyles, higher incomes, better health care, and more social opportunities—all associated with better brain health.

The share of the older population with dementia has fallen over the past two decades and continues to decline. Analysis of data from the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS) found that dementia declined from 11.6% in 2000 to 8.8% in 2012 among those ages 65 and older.7 Another study using data from NHATS found a decline from 13.0% in 2011 to 11.8% in 2015 among those ages 70 and older.8 The downward trend is likely the result of better brain health related to higher levels of education.9

Prevalence of Probable Dementia Among the U.S. Population Ages 70 and Older, 2015

Note: Excludes persons in nursing homes.

Source: Vicki A. Freedman et al., “Short-Term Changes in the Prevalence of Probable Dementia: An Analysis of the 2011–2015 National Health and Aging Trends Study,” Journals of Gerontology, Series B 73 (2018): S48-S56.

Dementia prevalence increases with age. About 5% of adults ages 70 to 79 had probable dementia in 2015, compared with 16% of adults ages 80 to 89 and 31% of adults ages 90 and older. As the U.S. population grows older, the number of people with dementia is projected to increase sharply.10

Women are slightly more likely to have dementia than men. Among adults ages 70 and older, 10.1% of women and 9.6% of men had probable dementia.

Non-Hispanic whites have lower rates of dementia than other racial/ethnic groups. The rates of probable dementia among “Hispanic and other” racial/ethnic minorities ages 70 and older (17%) was double the rate among non-Hispanic white older adults (8%). Recent declines in dementia prevalence have been concentrated among non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black groups, whereas dementia prevalence has been persistently higher among the Hispanic/Latino population.11

Racial/ethnic differences in dementia prevalence are linked to immigrant status. Researchers have found that non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and other immigrants have higher rates of dementia compared with their U.S.-born counterparts. However, the opposite is true for non-Hispanic black immigrants, who are less likely to have dementia than U.S.-born, non-Hispanic African Americans.12

Married older people may have a lower risk of dementia than their unmarried counterparts. A study that tracked a nationally representative set of HRS participants over 14 years found that married people were less likely to experience dementia as they aged.13 By contrast, unmarried older adults—including those who were cohabiting, divorced/separated, widowed, or never married—had significantly higher odds of developing dementia over the course of the study.

Divorcees were about twice as likely as married people to develop dementia, with divorced men facing a greater risk than divorced women. The researchers’ analysis showed that differing economic resources and health-related factors (such as behaviors and chronic conditions) only partly accounted for higher dementia risk among unmarried people.

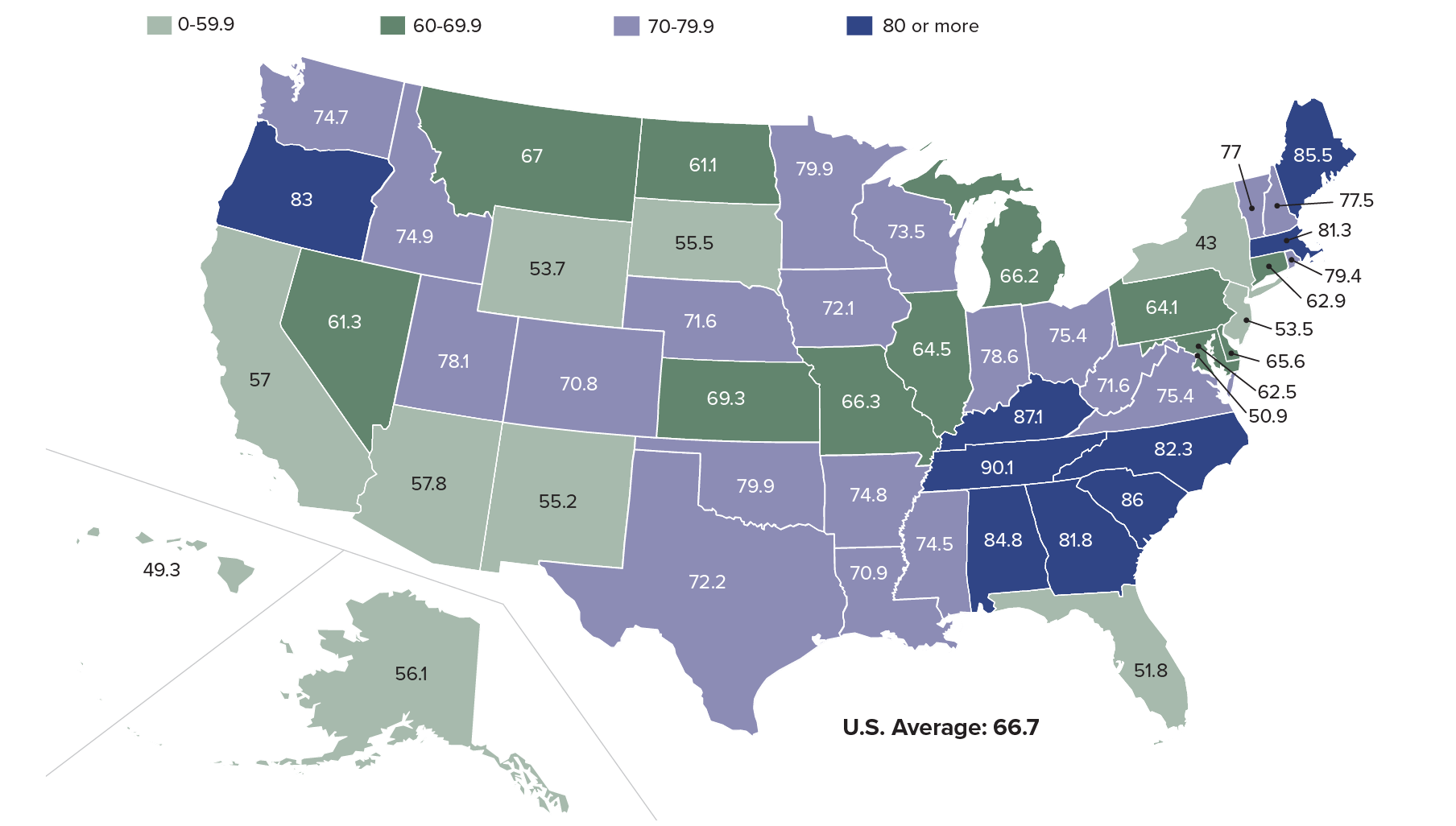

The rate of Americans who die from dementia is increasing. In 2017, 66.7 deaths per 100,000 people were attributed to dementia, compared with 30.5 in 2000, according to a recent report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).14 Part of this increase may reflect the decline in mortality due to other chronic conditions, such as heart disease. Since many people may go undiagnosed, published death rates may understate dementia-related deaths.

In 2017, Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee were among the states with the highest age-adjusted death rates for dementia (more than 80 deaths per 100,000 population; see map). Maine, Massachusetts, and Oregon also had relatively high death rates from the disease, whereas New York had the lowest death rate for dementia (43 per 100,000).

Geographic variations across states may reflect different approaches to diagnosing dementia, different guidelines for coding dementia, and differences in the socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic composition of populations across geographic areas.15 The CDC adjusts for age differences across states to ensure that differences in death rates between geographic areas are not due to differences in the age distribution of the populations being compared.

Age-Adjusted Death Rates per 100,000 by State, 2017

Source: Ellen A. Kramarow and Betzaida Tejada-Vera, “Dementia Mortality in the United States, 2000-2017,” National Vital Statistics Reports 68, no. 2 (2019).

| wdt_ID | States | Deaths | Rate per 100,000 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 261,914.0 | 66.7 |

| 2 | Alabama | 4,815.0 | 84.8 |

| 3 | Alaska | 253.0 | 56.1 |

| 4 | Arizona | 5,045.0 | 57.8 |

| 5 | Arkansas | 2,735.0 | 74.8 |

| 6 | California | 25,017.0 | 57.0 |

| 7 | Colorado | 3,806.0 | 70.8 |

| 8 | Connecticut | 3,351.0 | 62.9 |

| 9 | Delaware | 881.0 | 65.6 |

| 10 | District of Columbia | 358.0 | 50.9 |

| 11 | Florida | 17,523.0 | 51.8 |

| 12 | Georgia | 7,659.0 | 81.8 |

| 13 | Hawaii | 1,151.0 | 49.3 |

| 14 | Idaho | 1,371.0 | 74.9 |

| 15 | Illinois | 10,147.0 | 64.5 |

| 16 | Indiana | 6,190.0 | 78.6 |

| 17 | Iowa | 3,270.0 | 72.1 |

| 18 | Kansas | 2,590.0 | 69.3 |

| 19 | Kentucky | 4,404.0 | 87.1 |

| 20 | Louisiana | 3,564.0 | 70.9 |

| 21 | Maine | 1,705.0 | 85.5 |

| 22 | Maryland | 4,403.0 | 62.5 |

| 23 | Massachusetts | 7,584.0 | 81.3 |

| 24 | Michigan | 8,523.0 | 66.2 |

| 25 | Minnesota | 5,672.0 | 79.9 |

In 2015, about 85% of Americans with probable dementia lived at home in the community or in supportive care settings (such as assisted living or personal care homes), whereas about 15% lived in nursing facilities.16 Among those with dementia living in settings other than nursing homes in 2011, 80% were in traditional community settings and about 20% lived in residential care settings (about 15% in assisted living and another 5% in independent living).17

The availability and capacity of family and other informal caregivers, income and asset levels, and the type of care needed all contribute to determining the setting in which older adults with dementia live. Eligibility for government programs and the availability of services, some of which vary by state, also play key roles.

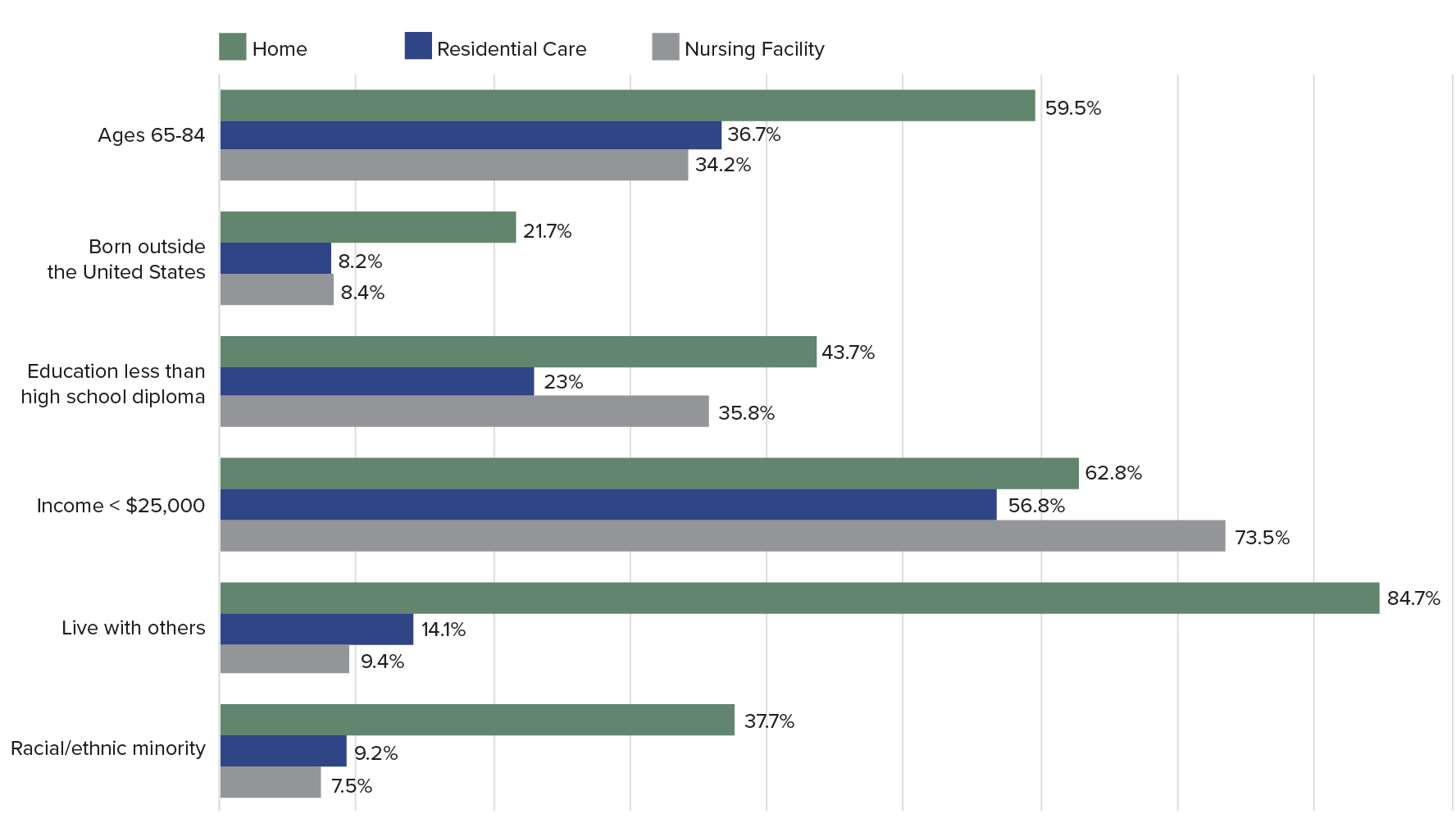

People with advancing dementia who live at home are more likely to be racial and ethnic minorities, foreign born, and less educated. Krista Harrison and colleagues used NHATS data to examine the living arrangements of older adults with advancing dementia, defined as probable dementia that interferes with some aspects of personal care or household activities.18 Those living at home were much more likely to be black or Hispanic, not born in the United States, and lack a high school diploma—characteristics that are linked to socioeconomic disadvantage and health disparities (see Figure 2).

People with advancing dementia who live at home have more social support but also more chronic conditions. Older adults with advancing dementia residing at home tend to have more social support (a partner, larger social networks) and less functional impairment than their counterparts in residential care or nursing facilities. At the same time, home-dwelling people with dementia tend to have worse overall health and more chronic conditions.

The researchers question whether “living at home with dementia is achieved at the expense of trade-offs on family members’ mental, physical, and financial well-being, or results in disparities in unmet needs or access to high-quality dementia care.”

Most older adults with cognitive impairment who live alone rely on an adult child for assistance. Milder forms of cognitive impairment often precede a dementia diagnosis. For those with cognitive impairment residing alone, another analysis of NHATS data showed that in 2011, two in three (66%) relied on an adult son or daughter for assistance that enabled them to live independently.19 About one in eight relied on paid professionals as primary caregivers. Most of the adults with cognitive impairment were older, widowed females.

Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics of Medicare Enrollees Ages 65 and Older With Advancing Dementia, by Care Setting

Notes: All differences comparing home versus residential care versus nursing home significant at P > .05. The amount used in many states in 2012 to determine eligibility criteria for Medicaid-paid nursing home care was $25,000.

Source: Krista L. Harrison et al., “Care Settings and Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults With Moderately Severe Dementia,” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 67, no. 9 (2019): 1907-12.

Most older people, including those with dementia and their caregivers, prefer to receive care at home rather than in nursing facilities, and many families take pride in providing care themselves. Reflecting these preferences, an increasing proportion of Medicaid funds for lower-income older adults are being spent on home- and community-based services and support (such as personal care assistance and home-delivered meals) rather than on institutional care.20 These services vary considerably by state and aim to enable people with dementia to continue living at home or in a residential care setting rather than in more costly nursing facilities.

Higher-income people with dementia are somewhat more likely to live in residential care, whereas lower-income people with dementia are more likely to live in nursing homes or at home.21 Medicare and Medicaid policies contribute to shaping these residential patterns. Medicare does not pay for most long-term support and care in either a residential care setting, such as an assisted living facility, or a nursing home. For lower-income older adults (or those who spend down their savings or assets to qualify), Medicaid may pay a portion of supportive care costs, primarily in nursing facilities, depending on the state. The median annual cost of assisted living, one type of residential care that typically provides social but not medical support, was $49,000 in 2019. The median annual cost of a nursing facility that provides medical support, which often serves lower-income older people with Medicaid coverage, was $90,000.22

Middle-income people with dementia are less likely to receive paid care. An analysis of NHATS data by Jennifer Reckrey and colleagues showed that only one in four older adults with probable dementia living at home (25.5%) received paid care in 2015.23 Among the fraction with advanced dementia, only about half (48.3%) received paid care. Analysis showed that those receiving paid care were more likely to qualify for Medicaid, be male, unmarried, have fewer children, and require more help with daily activities than their peers without paid care.

The researchers observed that older adults with probable dementia in the lowest and highest income groups (below $12,000 and above $43,000 annually) were somewhat more likely to receive paid care, reflecting that “not just functional need but also financial resources and Medicaid eligibility” contribute to patterns of where older people with dementia live.

“[T]he middle class, who neither qualify for Medicaid-funded home care nor have the means to pay for significant paid caregiving out of pocket, face a unique challenge: They must either rely solely on family caregivers to meet their needs or pay out of pocket for paid caregivers until their wealth is exhausted and they become Medicaid eligible,” the researchers write.

Dementia care is more costly than other conditions and puts a disproportionate burden on families. What people with dementia need most is supervision and help with personal care and household activities—services not covered by Medicare—whereas the drugs or surgeries commonly used to treat conditions such as heart disease and cancer are covered.

“The lifetime cost of dementia is high,” report researchers from the RAND Corporation. Using HRS data, RAND researchers found that those who live with dementia for at least six months pay, on average, $38,500 more out of pocket from age 65 to death (adjusting for length of life, demographics, lifetime earnings, and other health conditions).24 These dementia-related costs are nearly all composed of spending on nursing homes.

Similarly, Amy Kelley and colleagues used HRS data to show that health care for Medicare beneficiaries in the last five years of life was far more costly and involved significantly higher uncovered out-of-pocket costs for those with dementia than for those with heart disease, cancer, or other medical conditions.25 Out-of-pocket costs averaged $62,000 for people with dementia, more than 80% higher than for someone with heart disease or cancer.

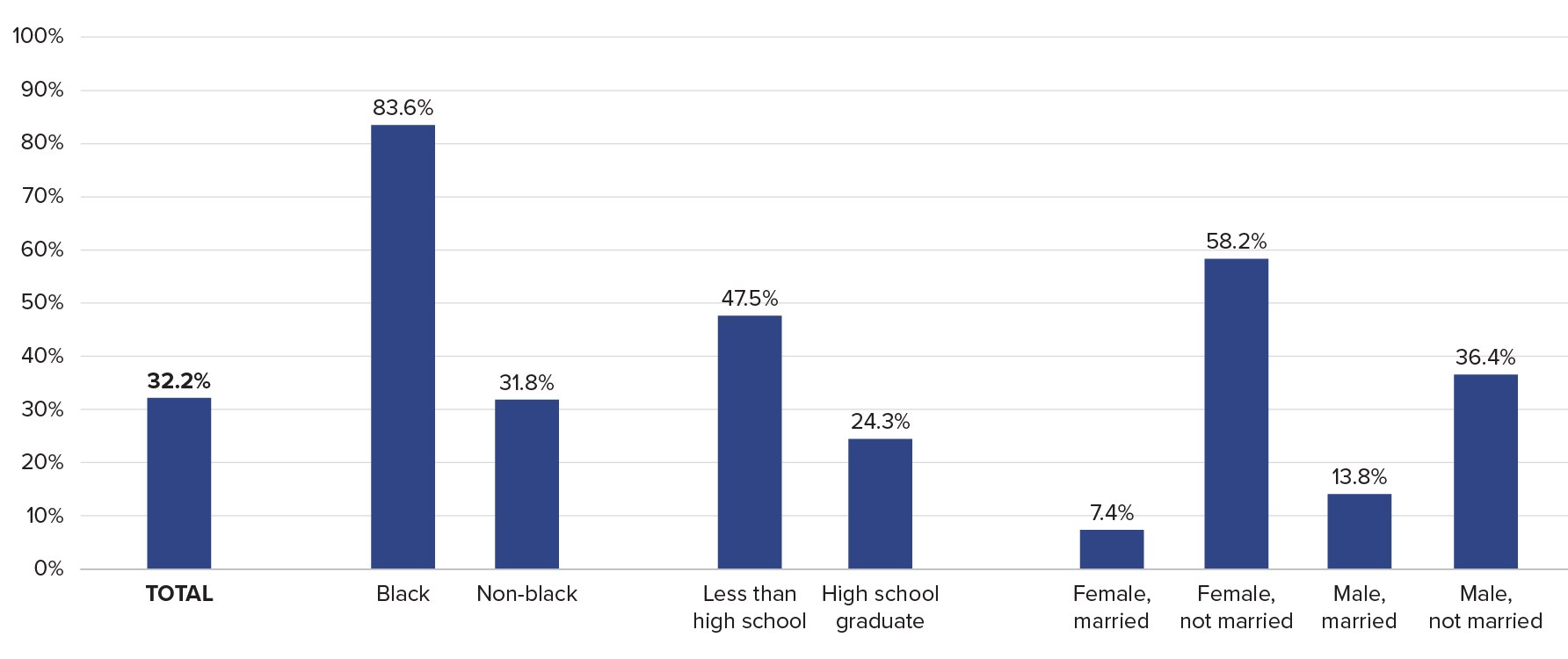

Families of older people with dementia also spent a larger share of family assets for care in the last five years of life than families of those with other conditions. During these years, families spent nearly a third of their wealth (32%) on dementia care, compared with 11% for other diseases. African Americans, people with less than a high school education, and unmarried or widowed women faced the greatest economic burdens (see Figure 3).

The challenge, according to the researchers, is that “Medicare does not cover health-related expenses most valuable to those with chronic diseases or a life-limiting illness, such as homecare services, equipment, and non-rehabilitative nursing home care.” These costs are “largely borne by individuals and families, particularly among vulnerable subgroups.”26

Out-of-Pocket Expenditures on Dementia During the Last Five Years of Life as a Percentage of Wealth, by Population Subgroup

Source: Amy Kelley et al., “The Burden of Health Care Costs for Patients With Dementia in the Last Five Years of Life,” Annals of Internal Medicine 165, no. 3 (2015): 729-36.

When intangible costs are considered, caring for an older parent with dementia at home may be as costly as institutional care. Norma Coe and colleagues calculated the median direct and indirect costs to a daughter who cares for her mother who cannot be left alone.27 Their estimate accounted for not just a caregiver daughter’s lost earnings but also her future employability, lost leisure time, and impact on her well-being. Their findings suggest that costs total nearly $200,000 over two years, about the same as full-time care in a nursing facility.

Most U.S. adults ages 65 and older do not have long-term care insurance. In 2014, just 11% of older adults had such coverage, which protects them from catastrophic expenses related to long-term care support and dementia care if they did not qualify for Medicaid, analysis of HRS data showed.28 Caroline Pearson and colleagues estimated that by 2029, only about half of middle-income seniors ages 75 and older will have sufficient financial resources to pay for supportive care in a private residential setting (such as assisted living) if they develop conditions such as dementia.29

lthough older adults with probable dementia represent only about 10% of people ages 65 and older, they receive 41% of all care hours, and their informal caregivers make up one-third of all caregivers, according to data from the 2011 NHATS and the related National Study of Caregiving.30 Overall, daughters provide the bulk of unpaid care hours for people with dementia (39%), followed by spouses (25%), sons (17%), and other family and friends (20%). Older adults with dementia have larger caregiving networks than those without dementia and are twice as likely to have multiple caregivers sharing tasks.31

Caring for people with dementia living at home is the most time-intensive type of elder care. Among adults ages 65 and older who received help, those with probable dementia received many more hours of care, averaging 92 hours per month versus 68 for those without dementia.32 Caregiving was particularly time consuming for spouses or daughters or those who lived with the care recipient, totaling 145, 102, and 143 mean hours of caregiving per month, respectively.33

Another team of researchers found even larger differences in care for people with and without dementia, using data from the HRS and a somewhat different definition of care and age range.34 Among adults ages 70 and older, those with probable dementia received more than twice as many hours of monthly care on average than adults without dementia: 171 hours versus 66 hours.

Many people with dementia rely on family members even when they have paid care. Reckrey and colleagues showed that among those with probable dementia who lived at home and had paid care providers, informal family caregivers provided more than half the total weekly care hours (83 hours of paid and family care).35 In addition, Judith Kasper and colleagues found that family caregiving does not end when older adults with dementia move into residential care settings such as assisted living; about 80% of older adults with dementia living in residential care had at least one family or unpaid caregiver assisting with self-care or household activities.36

Unpaid caregivers for older adults with dementia report more difficulties than caregivers of those without dementia, but the differences have narrowed. Many of the circumstances of unpaid caregivers of older adults with dementia improved between 1999 and 2015, according to Jennifer Wolff and colleagues.37 They found that among primary family caregivers of older adults with dementia, the proportion reporting substantial physical or financial difficulty declined during the 16-year period, and their use of respite care nearly doubled.

The recent decline in the share of U.S. older adults with dementia is good news for families and health care providers. However, researchers question whether dementia prevalence can continue to decline in tandem with higher rates of obesity and diabetes, which are both cardiovascular risk factors for certain types of dementia.

Research has also identified large and growing disparities in dementia risk by socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity, which could slow progress in reducing dementia prevalence. The high rate of probable dementia among Latinos is of particular concern, given the increasing numbers of Latinos in the U.S. population.38 A better understanding of the causes of the recent decrease in dementia prevalence can help shape interventions that could contribute to further declines, with tremendous implications for older Americans, their families, and the costs of public programs. Policies that address growing disparities in dementia risk by ensuring equity of access to the resources and environments that contribute to healthy cognitive function are crucial to the overall health of the U.S. older population.39

Regardless of trends in dementia prevalence, rapid population aging in the United States will contribute to an increase in the number of people living with dementia in the coming decades. Demographers foresee shifting family structures as the large baby-boom generation (ages 56 to 74 in 2020) approaches ages when the risk of dementia increases. Declines in marriage, high rates of divorce, and lower fertility over the last few decades mean that more baby boomers may reach older ages without a spouse and with fewer adult children, on average, than earlier generations to rely on for care, suggests Emily Agree.40 However, the chances of having a partner still living in later life may increase, depending on mortality trends.

As the pool of traditional family caregivers for older Americans changes, patterns of family care for people with dementia and other functional difficulties may shift as well. Policymakers can help by making paid care more affordable and implementing policies that support the emerging roles of siblings, friends, cohabiting partners, and more distant relatives as caregivers.

Given that family caregivers “provide the lion’s share of care in the community,” Reckrey and colleagues call for expanding direct payments to family members who provide care. They also argue for “new ways of making paid caregiving more accessible throughout the income spectrum” via Medicaid expansion, increased spending on home- and community-based services, and tax credits or tax deductions for paid caregiving expenditures.41

1 Estimates of the number of people living with dementia varies depending on definitions and sources used; the Alzheimer’s Association estimates that 5.8 million Americans were living with Alzheimer’s dementia in 2019—most of them age 65 or older.

2 James E. Galvin et al., “The AD8:A Brief Informant Interview to Detect Dementia,” Neurology 65, no. 4 (2005): 559-64.

3 Judith D. Kasper et al., “The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia on Family and Unpaid Caregiving to Older Adults,” Health Affairs34, no. 10 (2015): 1642-49; and Judith D. Kasper, Vicki A. Freedman, and Brenda Spillman, “Classification of Persons by Dementia Status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study,” Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Technical Paper #5 (2013), https://www.nhats.org/scripts/documents/DementiaTechnicalPaperJuly_2_4_2013_10_23_15.pdf.

4 National Institute on Aging, “Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic Guidelines,” https://nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-diagnostic-guidelines.

5 Krista L. Harrison et al., “Care Settings and Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults With Moderately Severe Dementia,” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 67, no. 9 (2019):1907-12; and Jennifer M. Reckrey et al., “Living in the Community With Dementia: Who Receives Paid Care?” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 68, no. 1 (2020): 186-91.

6 Eileen M. Crimmins et al., “Educational Differences in the Prevalence of Dementia and Life Expectancy With Dementia in the United States: Changes From 2000 to 2010,” Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences73, suppl. 1 (2019): S20-S28.

7 Kenneth M. Langa et al., “A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012,” JAMA Internal Medicine177, no. 1 (2017): 51-58. A separate study, using different methods, showed a more modest decline in dementia—from 12.0% in 2000 to 10.5% in 2012.

8 Vicki A. Freedman et al., “Short-Term Changes in the Prevalence of Probable Dementia: An Analysis of the 2011-2015 National Health and Aging Trends Study,” Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences73, suppl. 1 (2018): S48-S56.

9 Langa et al., “A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012.”

10 Freedman et al., “Short-Term Changes in the Prevalence of Probable Dementia.”

11 Freedman et al., “Short-Term Changes in the Prevalence of Probable Dementia.”

12 Heehyul Moon et al., “Dementia Prevalence in Older Adults: Variation by Race/Ethnicity and Immigrant Status,” American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 27, no. 3 (2019): 241-50.

13 Hui Liu et al., “Marital Status and Dementia: Evidence From the Health and Retirement Study,” Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences (2019).

14 Ellen A. Kramarow and Betzaida Tejada-Vera, “Dementia Mortality in the United States, 2000-2017,” National Vital Statistics Reports68, no. 2 (2019): 1-29.

15 Kramarow and Tejada-Vera, “Dementia Mortality in the United States, 2000-2017.”

16 This calculation assumes half of nursing home residents have dementia. Winnie Chi et al., “Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Dementia and Their Caregivers: Key Indicators From the National Health and Aging Trends Study” (Washington, DC: The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, 2019), https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/260371/DemChartbook.pdf.

17 Judith D. Kasper et al., “The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia on Family and Unpaid Caregiving to Older Adults,” Health Affairs 34, no. 10 (2015): 1642-9.

18 Krista L. Harrison et al., “Care Settings and Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults With Moderately Severe Dementia,” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 67, no. 9 (2019): 1907-12.

19 Allison K. Gibson and Virginia E. Richardson, “Living Alone With Cognitive Impairment: Findings From the National Health and Aging Trends Study,” American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias 32, no. 1 (2017): 56-62.

20 Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), “Home- and Community-Based Services,” http://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/home-and-community-based-services/.

21 Harrison et al., “Care Settings and Clinical Characteristics of Older Adults With Moderately Severe Dementia.”

22 Genworth, “Cost of Care Survey, 2019,” www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html.

23 Jennifer M. Reckrey et al., “Living in the Community With Dementia: Who Receives Paid Care?” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 68, no. 1 (2020): 186-91.

24 Péter Hudomiet, Michael D. Hurd, and Susann Rohwedder, “The Relationship Between Lifetime Out-of-Pocket Medical Expenditures, Dementia, and Socioeconomic Status in the U.S.,” The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 14 (2019).

25 Amy S. Kelley et al., “The Burden of Health Care Costs for Patients With Dementia in the Last Five Years of Life,” Annals of Internal Medicine 163, no. 10 (2015): 729-36.

26 Kelley et al., “The Burden of Health Care Costs for Patients With Dementia in the Last Five Years of Life.”

27 Norma B. Coe, Meghan M. Skira, and Eric B. Larson, “A Comprehensive Measure of the Costs of Caring for a Parent: Differences According to Functional Status,” Journal of the American Geriatric Society 66, no. 10 (2018): 2003-8.

28 Richard W. Johnson, “Who Is Covered by Private Long-Term Care Insurance?” Urban Institute Brief, August 2, 2016, www.urban.org/research/publication/who-covered-private-long-term-care-insurance.

29 Caroline F. Pearson et al., “The Forgotten Middle: Many Middle-Income Seniors Will Have Insufficient Resources for Housing and Health Care,” Health Affairs 38, no. 5 (2019): 851-9.

30 Kasper et al., “The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia on Family and Unpaid Caregiving to Older Adults.”

31 Brenda C. Spillman et al., “Change Over Time in Caregiving Networks for Older Adults With and Without Dementia,” Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences (2019).

32 Kasper et al., “The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia on Family and Unpaid Caregiving to Older Adults.”

33 Kasper et al., “The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia on Family and Unpaid Caregiving to Older Adults.”

34 Esther M. Friedman et al., “U.S. Prevalence and Predictors of Informal Caregiving for Dementia,” Health Affairs 34, no. 10 (2015): 1637-41.

35 Reckrey et al., “Living in the Community With Dementia: Who Receives Paid Care?”

36 Kasper et al., “The Disproportionate Impact of Dementia on Family and Unpaid Caregiving to Older Adults.”

37 Jennifer L. Wolff et al., “Family Caregivers of Older Adults, 1999-2015: Trends in Characteristics, Circumstances, and Role-Related Appraisal,” Gerontologist 58, no. 6 (2018): 1021-32.

38 Freedman et al., “Short-Term Changes in the Prevalence of Probable Dementia.”

39 Langa et al., “A Comparison of the Prevalence of Dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012.”

40 Emily M. Agree, “Demography of Aging and the Family,” in Future Directions for the Demography of Aging: Proceedings of a Workshop (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2018).

41 Reckrey et al., “Living in the Community With Dementia: Who Receives Paid Care?”