Today’s Research on Aging, No. 44 (2024)

Quick Links

Older adults with the most supportive relationships were aging one to two years slower than those who lacked such ties.

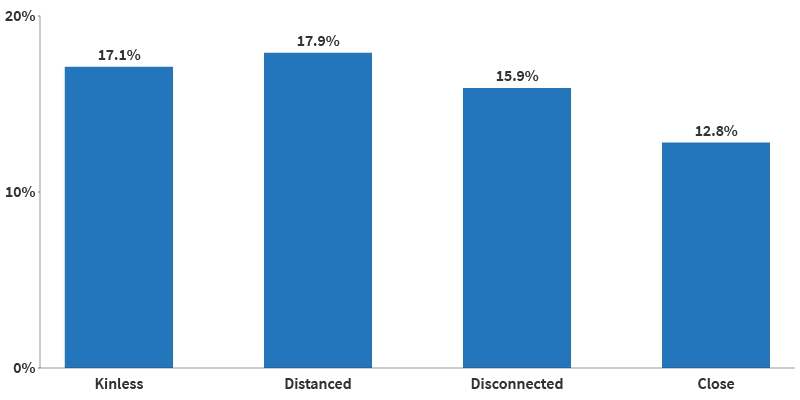

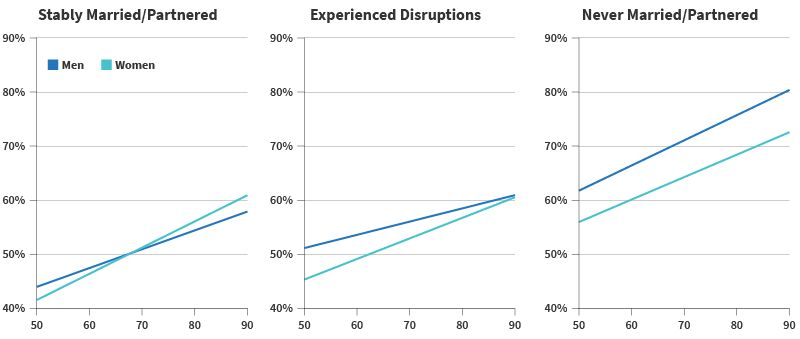

Being unmarried, male, and having low education and income levels increased the odds of being socially isolated.

Companionship and emergency help mattered most to older adults.

When faced with traumatic events, older adults with fewer confidants living nearby showed more severe depression symptoms than those with more close friends in their neighborhood.

Even two years of living alone is linked to about a 10% increase in the risk of dementia.

Older adults who had less in-person time with family and friends and more phone calls during the first year of the pandemic were more likely to experience loneliness.

References

- Kelly E. Rentscher et al., “Social Relationships and Epigenetic Aging in Older Adulthood: Results From the Health and Retirement Study,” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 114, (2023): 349-59.

- Linda Waite and Yiang Li, “Bringing the Social World Into Our Understanding of Health,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Columbus, April 2024.

- Michaela G. Cuneo et al., “Positive Psychosocial Factors and Oxytocin in the Ovarian Tumor Microenvironment,” Psychosomatic Medicine 83, no. 5 (2021): 417-22.

- Dannielle E. Kelley, et al., “Dyadic Associations Between Perceived Social Support and Cancer Patient and Caregiver Health: An Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling Approach,” Psycho-oncology 28, no. 7 (2019): 1453-60.

- Won-Tak Joo, “Educational Gradient in Social Network Changes at Disease Diagnosis,” Social Science & Medicine 317 (2023): 115626.

- Karen L. Fingerman, et al., “Functional Limitations, Social Integration, and Daily Activities in Late Life,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 76, no. 10 (2021): 1937-47.

- Sophie Mitra, Debra L. Brucker, and Katie M Jajtner, “Wellbeing at Older Ages: Towards an Inclusive and Multidimensional Measure,” Disability and Health Journal 13, no. 4 (2020): 100926.

- Dan Zhang et al. “What Could Interfere with a Good Night’s Sleep? The Risks of Social Isolation, Poor Physical and Psychological Health Among Older Adults in China,” Research on Aging 44, nos. 7-8 (2022): 519-30.

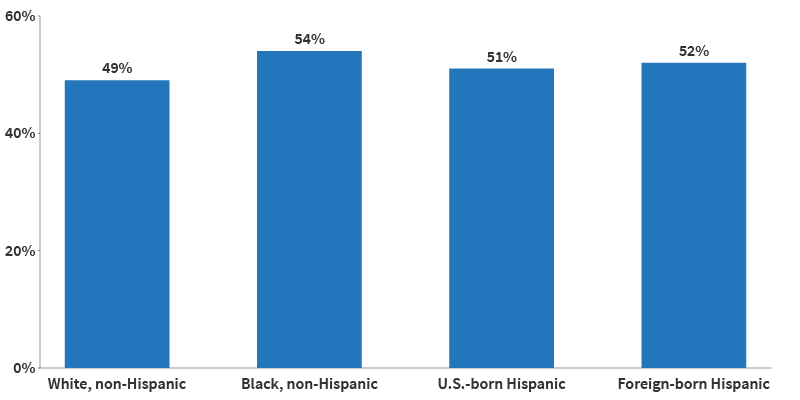

- Debra Umberson and Rachel Donnelly, “Social Isolation: An Unequally Distributed Health Hazard,” Annual Review of Sociology 49, no. 1 (2023): 379-99.

- Thomas K. M. Cudjoe et al., “The Epidemiology of Social Isolation: National Health and Aging Trends Study,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 75, no. 1 (2020): 107-13.

- Kaulie Watson, “Social Isolation Can Begin as Early as Adolescence, Research Shows,” The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts, July 20, 2023.

- Jordan Weiss, Leora E. Lawton, and Claude S. Fischer, “Life Course Transitions and Changes in Network Ties Among Younger and Older Adults,” Advances in Life Course Research 52 (2022): 100478.

- James Iveniuk, “Social Networks, Role-Relationships, and Personality in Older Adulthood,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74, no. 5, July 2019, 815–26.

- Sarah E. Patterson and Rachel Margolis, “Family Ties and Older Adult Well-Being: Incorporating Social Networks and Proximity,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 78, no. 12 (2023): 2080-9.

- Jon Meerdink, “New Paper Explores the Impact of Family Ties on Older Adults,” University of Michigan Institute for Social Research, November 15, 2023.

- Stephanie T. Child and Leora E. Lawton, “Personal Networks and Associations With Psychological Distress Among Young and Older Adults,” Social Science & Medicine 246 (2020): 112714.

- Stephanie T. Child and Leora Lawton, “Loneliness and Social Isolation Among Young and Late Middle-Age Adults: Associations With Personal Networks and Social Participation,” Aging & Mental Health 23, no. 2 (2019): 196-204.

- Abbey M. Hamlin et al., “Social Engagement and Its Links to Cognition Differ Across Non-Hispanic Black and White Older Adults,” Neuropsychology 36, no. 7 (2022): 640-50.

- Debra Umberson, Zhiyong Lin, and Hyungmin Cha, “Gender and Social Isolation Across the Life Course,” Journal of Health and Social behavior 63, no. 3 (2022): 319-35.

- Kimberly A. Dill-McFarland et al., “Close Social Relationships Correlate With Human Gut Microbiota Composition,” Scientific Reports 9, no. 1 (2019): 703.

- Mieke Beth Thomeer, Amanda Pollitt, and Debra Umberson, “Support in Response to a Spouse’s Distress: Comparing Women and Men in Same-Sex and Different-Sex Marriages,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 38, no. 5 (2021): 1513-34.

- Shira Offer, “They Drive Me Crazy: Difficult Social Ties and Subjective Well-Being,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 61, no. 4 (2020): 418-36.

- Claudia Recksiedler and Robert S. Stawski, “Marital Transitions and Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults: Examining Educational Differences,” Gerontology 65, no. 4 (2019): 407-18.

- James Iveniuk, Peter Donnelly, and Louise Hawkley, “The Death of Confidants and Changes in Older Adults’ Social Lives,” Research on Aging 42, nos. 7-8 (2020): 236-46.

- Mark Mather and Paola Scommegna, “How Neighborhoods Affect the Health and Well-Being of Older Americans,” Today’s Research on Aging, no. 35 (2017).

- Alyssa Goldman and Jayant Pinto, “Sensory Health Among Older Adults in the United States: A Neighborhood Context Approach,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B; Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 79, no. 5, (May).

- Oanh L. Meyer et al., “Neighborhood Characteristics and Caregiver Depressive Symptoms in the National Study of Caregiving,” Journal of Aging and Health 34, no. 6-8 (2022): 1005-15.

- Keunbok Lee, “Different Discussion Partners and Their Effect on Depression Among Older Adults,” Social Sciences 10, no. 6 (2021): 215.

- Xue Zhang, Danielle Rhubart, and Shannon Monnat, “Social Infrastructure Availability and Suicide Rates Among Working-Age Adults in the United States,” Socius 10 (2024).

- Benjamin A Shaw, Tse-Chuan Yang, and Seulki Kim, “Living Alone During Old Age and the Risk of Dementia: Assessing the Cumulative Risk of Living Alone,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 78, no. 2 (2023): 293-301.

- Yeon Jin Choi, Jennifer A. Ailshire, and Eileen M. Crimmins, “Living Alone, Social Networks in Neighbourhoods, and Daily Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults in the USA,” Public Health Nutrition 23,18 (2020): 3315-23.

- Namkee G. Choi et al., “COVID-19 and Loneliness Among Older Adults: Associations With Mode of Family/Friend Contacts and Social Participation,” Clinical Gerontologist 45, no. 2 (2022): 390-402 and Louise C. Hawkley et al., “Can Remote Social Contact Replace In-Person Contact to Protect Mental Health Among Older Adults?” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 69, no. 11 (2021): 3063-5.

- Amanda Zhang et al., “Can Digital Communication Protect Against Depression for Older Adults With Hearing and Vision Impairment During COVID-19?” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 78, no. 4 (2023): 629-38.

- Yijung K. Kim, and Karen L. Fingerman, “Daily Social Media Use, Social Ties, and Emotional Well-Being in Later Life,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 39, no. 6 (2022): 1794-1813.

- Jeffrey G. Snodgrass et al. “Social Connection and Gene Regulation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Divergent Patterns for Online and In-Person Interaction,” Psychoneuroendocrinology 144 (2022): 105885.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “New Surgeon General Advisory Raises Alarm About the Devastating Impact of the Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation in the United States,” May 3, 2023.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “New Surgeon General Advisory Raises Alarm About the Devastating Impact of the Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation in the United States.”