Top 10 Countries Closing Gender Gap

Since 2006, the World Economic Forum has issued a Global Gender Gap Index to review gender-based disparities around the world and track progress in closing the gap in four areas: educational attainment, health, economic participation, and political empowerment. According to The Global Gender Gap Report 2013, of the 110 countries measured since 2006, 86 percent have improved their performance every year, while 14 percent have shown widened gaps.1

Scandinavian Countries Annual List Toppers

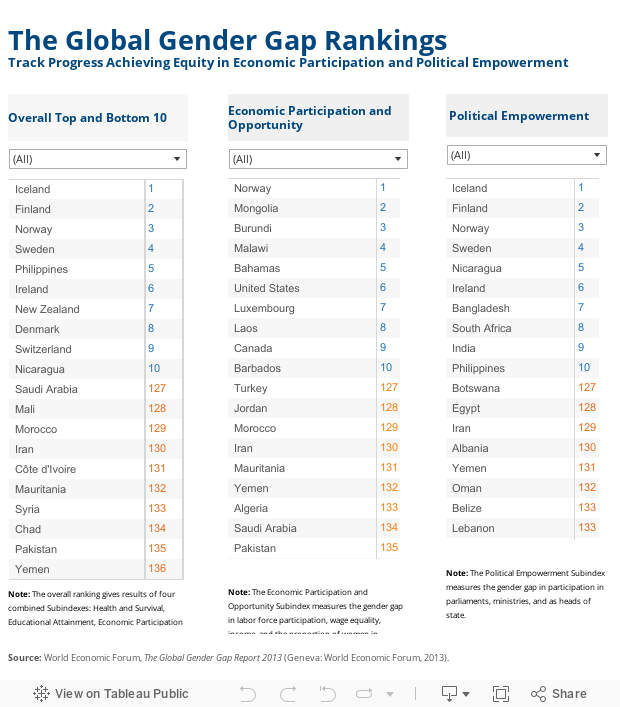

Annually the four top countries have been Iceland, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, largely because of long-standing equality in education and health; and the large proportion of women in the labor force, with small salary gaps and strong representation in high-skilled jobs (see data visualization for overall and selected rankings).2

var divElement = document.getElementById(‘viz1535749019058’); var vizElement = divElement.getElementsByTagName(‘object’)[0]; vizElement.style.width=’620px’;vizElement.style.height=’707px’; var scriptElement = document.createElement(‘script’); scriptElement.src = ‘https://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js’; vizElement.parentNode.insertBefore(scriptElement, vizElement);

The 136 countries covered in the 2013 report have closed almost 96 percent of the gap in health and almost 93 percent in educational attainment. These 136 countries represent 90 percent of the world’s population. Twenty-five countries have closed the gap in educational attainment, 33 countries have closed the gap in health and survival, and 10 countries have closed the gap in both of these categories.

Where differences emerge, and where countries have not made as much progress, are the gaps in economic participation and political empowerment: Only 60 percent of the economic gap and only 21 percent of the gap in political representation have been closed.3

Laura Liswood, secretary general of the Council of World Woman Leaders and vice chair of the forum’s Global Agenda Council on Women’s Empowerment, comments that the “Nordic nirvanas” can serve as a model for other countries to show the benefits of affirmative political mechanisms, such as minimums on the number of seats in parliament reserved for women. “Many countries now have such mechanisms in place,” says Liswood.4

Nicaragua’s Commitment to Women’s Political Involvement

For the second straight year, Nicaragua finished in the top 10 of countries making progress in closing gender gaps. Nicaragua ranks fifth among all countries on political empowerment and is one of those countries using affirmative mechanisms: Since 2000, political parties participating in National Assembly elections must submit an electoral list that includes 50 percent women.5

Overall, the Latin America and Caribbean region has shown the biggest improvement from last year among all countries, led by improvements in women’s economic participation and political empowerment. The region performs especially well on certain indicators, such as female legislators, senior officials, and managers: Ten of the 20 best-performing countries in that category are in Latin America.6

Joan Caivano, an expert on women’s leadership in Latin America and deputy to the president of the Inter-American Dialogue, thinks that a combination of factors contribute to Nicaragua’s performance, including a strong cadre of women leaders who were empowered by the Sandinista’s social programs of the 1980s; the legacy of Violeta Chamorro, head of state from 1990 to 1997; and the commitment of current president Daniel Ortega to populist programs as well as political appointments of women in ministries and parliament. In addition, many women lead in the nonprofit sector, heading up education, health, and housing programs.7

High Performers Link Women’s Education and Economic Growth

Report authors propose that closing gender gaps is important not only from an equity perspective, but also from an economic one: Research shows that investments in women’s education and use of female talent boost a country’s competitiveness.

Countries that have closed education gaps and have high levels of women’s economic participation—the Nordic countries, the United States, the Philippines, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia—demonstrate that their investment in education has returned strong economic growth, although gaps still persist among this group in senior positions, wages, and leadership. Report authors argue that a main driver of strong economic performance is the innovation that comes from creating a diverse environment in the workplace. They cite the benefits of more women working: The talent pool across leadership positions is larger, women’s decisionmaking tends to be less risky, and gender-equal teams may be more successful.

Where countries have closed education gaps, but still have low levels of women’s economic participation, women remain an untapped yet educated human resource. Research shows that investment in girls’ education reduces high fertility rates, lowers infant and child mortality, lowers maternal mortality, increases women’s labor force participation and earnings, and fosters educational investment in children.

From Data to Policies

The forum, an international nonprofit organization, convenes governments, business, and civil society to discuss pressing world topics and find solutions.

Critics argue that the Report does not include important measures of women’s empowerment. The health measure, for example, only looks at sex ratios at birth and life expectancies, and not at women’s reproductive health and rights. Nicaragua, with all its progress, still ranks 55th on the health gap.

According to Liswood, the Report is a place to start. She blogs that women face institutional and policy obstacles that make their work-life balance decisions complex. Policies such as family leave, child care, taxation, and workplace equality vary greatly from country to country and shape the parameters around women’s work decisions, “With these efforts, maybe we will be able to stop putting the onus solely on the individual for forces beyond her control and spread them where they equally belong.”8

References

- World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2013 (Davos, Switzerland: World Economic Forum, 2013).

- While many global indexes are tied to income levels, providing an advantage to high-income Nordic countries, the Global Gender Gap Index is disassociated from the income and resource level of an economy and instead seeks to measure how equitably the available income, resources, and opportunities are distributed between women and men.

- In March 2013, to complement the gap analysis in the Report, the Forum released an online repository of information highlighting company best practices that can help close economic gender gaps. Over the course of 2012, using the data from the Report to provide the context, they launched pilot Gender Parity Task Forces in three countries—Mexico, Turkey, and Japan—to foster public-private collaboration on closing the gender gaps in economic participation in each country for a three-year period by 10 percent. Based on initial successes with these Task Forces, other countries are now seeking to adopt this model.

- Interview with Laura Liswood on Jan. 17, 2014.

- QuotaProject: Global Database of Quotas for Women, “Nicaragua,” accessed at www.quotaproject.org/uid/countryview.cfm?CountryCode=NI, on Jan. 27, 2014.

- World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2013.

- Interview with Joan Caivano on Jan. 23, 2014.

- Laura Liswood, “So Can Women Have it All?” accessed at http://forumblog.org/2013/01/so-can-women-have-it-all/, on Jan. 15, 2014.