Paola Scommegna

Contributing Senior Writer

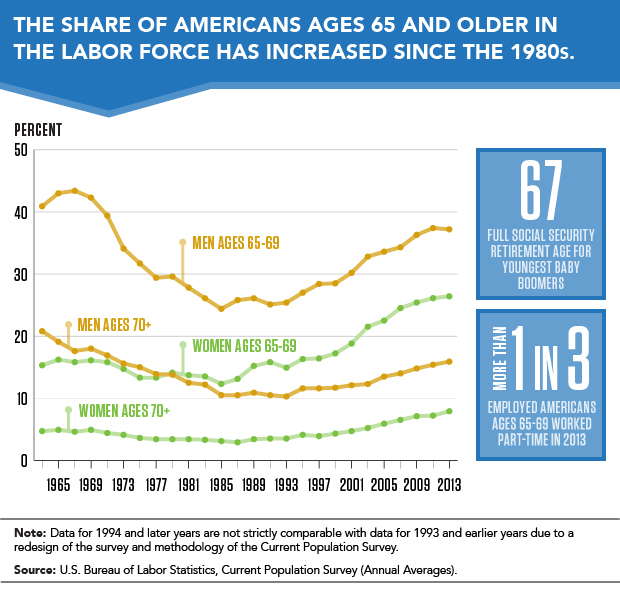

A growing share of Americans are working beyond their 65th birthdays, a reversal that began about 25 years ago (see figure). This upswing appears likely to continue as more members of the baby-boom generation (born between 1946 and 1964) reach traditional retirement ages.

A variety of financial incentives are keeping older people in the labor force. These include changes in the Social Security program that gradually raise the age when retirees can begin to receive full benefits to 67 for the youngest baby boomers. Also key are changes in the types of employer-sponsored retirement plans: Employers have shifted away from defined-benefit pensions that provide guaranteed payouts, often replacing them with 401(k) plans with payouts that depend on how much the retiree saves and how well the investments do.

Working longer is one way to enter retirement more financially secure, says Matthew Rutledge, research economist at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (CRR).

A recent CRR report identified a number of additional trends influencing decisions to postpone retirement over the past 25 years:

But will these factors continue to influence an ever-larger proportion of younger baby boomers, contributing to a further rise in the share of people working past 65?

Analysts disagree, according to Rutledge. “Some analysts believe that most of those factors have fully played themselves out,” he says. They argue that defined benefit pensions and retiree health insurance are almost entirely gone from the private sector, educational attainment has plateaued among the cohorts approaching retirement age, increases in obesity have offset other gains in health and longevity (like the decline of smoking and improved medical care), and blue-collar jobs have been rare for a generation.

But other analysts point to reasons these trends may continue to contribute to more people postponing retirement. For example, employers are not offering defined benefit pensions and retiree health insurance to more recent employees, but the number of long-tenured employees able to count on benefits from the old system is still significant and will continue to shrink, he notes.

In Rutledge’s view, analysts have not fully appreciated the profound effects the Great Recession is having on retirement decisions and will have for many years to come. “Financial markets have recovered, but if investors had to cash out to support themselves, or got skittish and bailed out, they may have missed out on that recovery, which means they may not have the financial resources to stop working,” he says. Additionally, workers who “experienced a long jobless spell but were lucky enough to find re-employment probably want to make up for the resources they depleted” by staying on the job.

But the recession also contributed to early retirements by “knocking a lot of people out of the labor force who may have preferred to keep working into their late 60s.” According to Rutledge’s research, jobless individuals ages 62 and older have little patience for the job search, and tend to stop searching and retire within a year of losing a job.1 “If they don’t come back—and ‘unretirement’ is common, but hardly the norm—then retirement ages will be lower than they would have been if the recession had been a more normal downturn.”

In addition, diminished job prospects during the recession led many people to apply for disability insurance and record numbers began receiving benefits. The Social Security Administration “has done their best to try to give disability beneficiaries incentives to return to work, but research indicates that not very many recipients are healthy enough to even look for a job or stay with one for long enough to disqualify themselves,” he reports.

Federal disability insurance (DI) under the Social Security program has traditionally removed mostly low-educated workers from the pool of potential retirees, and this group likely had fairly early retirement ages even if they had not been on DI benefits, Rutledge explains. But the recent increase in disability recipients could have an impact on labor force participation rates because more highly educated workers are receiving DI as well. “Due to the increasing prevalence of mental illness as a disabling condition, higher-educated individuals are getting on DI, likely cutting off their careers much earlier than we would have projected,” he says.

Continued stagnant wages for low- and middle-income workers are likely to reduce the incentive to stay in the workforce. “If people don’t see their efforts rewarded with wage growth that actually keeps up with the cost of living and with their expectations about how much they should be making near the ends of their careers, then they’re likely to decide it’s not worth working,” says Rutledge.

The availability of part-time positions will also influence whether older Americans remain on the job or retire early. While many older employees prefer to transition slowly to full retirement by working part-time initially, some employers are reluctant to allow part-time work. Data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey show that among employed 65-to-69-year-olds in 2013, nearly one-third of men (31 percent) and almost one-half of women (46 percent) were working part-time.2 Among those ages 70 and older still in the workforce, an even larger share was working part-time (44 percent of men and 55 percent of women).

Finally, new changes in the Social Security program could be effective in encouraging older individuals to remain in the workforce longer and delay claiming benefits. “Some reform will be needed—especially to disability insurance, which has less than two years left before its Trust Fund is exhausted.”

Paola Scommegna is a senior writer/editor at the Population Reference Bureau.