Heidi Worley

Former Program Director

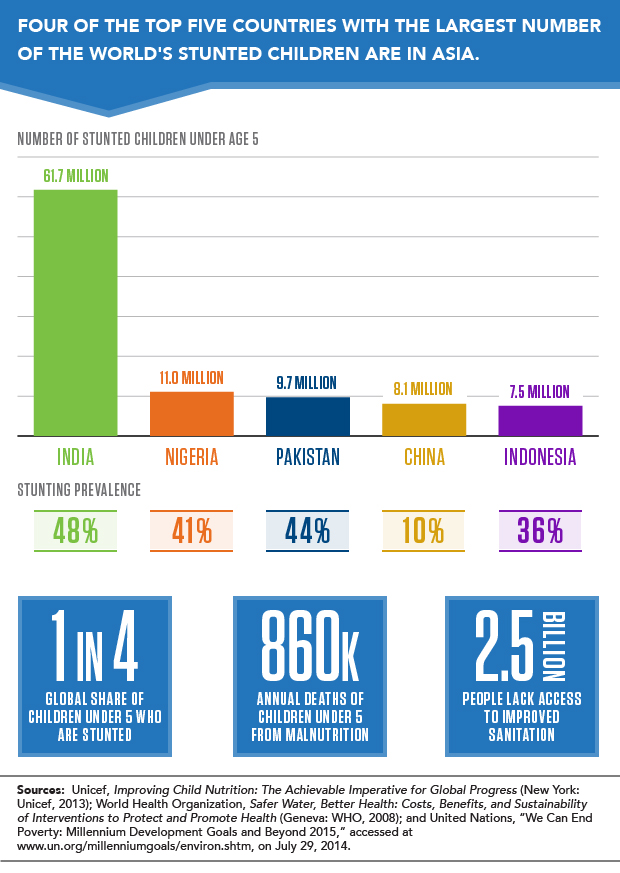

Globally, an estimated one in four children under age 5 suffer from stunting, a form of malnutrition in which children are shorter than normal for their age.1 In India, almost 62 million children (48 percent) across all income groups are stunted (see figure). Stunting, or chronic malnutrition, is accompanied by a host of problems—weak immune systems, risk of sickness and disease, arrested cognitive and physical development, and a greater risk of dying before age 5.

Stunting happens over time and can be caused by inadequate maternal nutrition, poor feeding practices, or substandard food quality as well as frequent infections. The high rate of stunting in India is surprising given its economic growth, especially in contrast to sub-Saharan Africa where GDP is lower.

A recent story in the New York Times explored the link between high rates of child malnutrition in India and the country’s poor sanitation, shedding light on a potential cause of a protracted problem. For India, the issue is not a lack of food, but rather a lack of toilets for its population—one-half of India’s population, at least 620 million people, defecates outside.

The interaction between diarrheal disease and malnutrition is well established. Diarrhea is often caused by a lack of clean water for proper hand-washing. A lack of toilets further exacerbates the problem as feces on the ground contribute to contaminated drinking water and water resources in general.

The World Health Organization estimates that 50 percent of malnutrition is associated with repeated diarrhea or intestinal worm infections from unsafe water or poor sanitation or hygiene.2

Stunting can stem from enteropathy, a chronic illness caused by inflammation that keeps the body from absorbing calories and nutrients. Children who are exposed to open defecation or who don’t have a clean water supply may ingest bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites that cause intestinal infection; chronic inflammation in a child’s gastrointestinal track is linked to stunting and anemia, and puts children at risk for poor early childhood development.3

Many organizations have adopted an integrated approach to improve water, sanitation, and hygiene, known as WASH programs. One of the United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals is to halve by 2015 the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation. However, despite progress, 2.5 billion people in developing countries still lack access to improved sanitation facilities.4

“The story is not so simple,” says Rhonda Smith, associate vice president for International Programs at the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), who leads PRB’s efforts to reduce malnutrition in pregnant women and children under the RENEW project. According to Smith, several factors contribute to stunting. “Women’s low status in many segments of Indian society can have a significant effect on children’s nutrition. Limited decisionmaking authority means less control over food purchases and less ability to control how food is distributed among family members.”

Indeed, researchers have found that women’s relative bargaining power within the household determined how resources are directed to support feeding practices, prenatal and birthing care, and treatment for illness and immunizations.5 In India, studies found that a higher share of children whose mothers had below primary education or were younger than 20 were stunted, but that children living in female-headed households were less stunted, and that reduced stunting was associated with whether women were able to make decisions to travel outside the home and whether they were able to make decisions about household purchases.6

Diarrhea prevalence drops substantially only if open defecation is completely eliminated.7 Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, pledged to add 5 million toilets by the end of September of this year.8

Unfortunately, the toilets that have been built in India have sometimes gone unused or have been used to store tools, grain, or building materials.9 Changes in social norms and behaviors must change too. According to Unicef, India has revamped its national sanitation program to focus less on subsidized toilet construction and more on helping the population understand the benefits of toilets. Dean Spears, an economist and visiting researcher at the Delhi School of Economics, writes, “Open defecation is everybody’s problem. It is the quintessential ‘public bad’ with negative spillover effects even on households that do not practice it.”