Mark Mather

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

February 5, 2016

Associate Vice President, U.S. Programs

Former Associate Vice President, International Programs

A new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report on female genital mutilation/cutting in the United States was released in January 2016, providing additional information on women and girls at risk.

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), involving partial or total removal of the external genitals of girls and women for religious, cultural, or other nonmedical reasons, has devastating immediate and long-term health and social effects, especially related to childbirth. This type of violence against women violates women’s human rights. There are more than 3 million girls, the majority in sub-Saharan Africa, who are at risk of cutting/mutilation each year. In Djibouti, Guinea, and Somalia, nine in 10 girls ages 15 to 19 have been subjected to FGM/C. Some countries in Africa have recently outlawed the practice, including Guinea-Bissau, but progress in eliminating the harmful traditional practice has been slow.1 Although FGM/C is most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, global migration patterns have increased the risk of FGM/C among women and girls living in developed countries, including the United States.

Increasingly, policymakers, NGOs, and community leaders are speaking out against this harmful traditional practice. As more information becomes available about the practice, it is clear that FGM/C needs to be unmasked and challenged around the world.

The U.S. Congress passed a law in 1996 making it illegal to perform FGM/C and 23 states have laws against the practice.2 Despite decades of work in the United States and globally to prevent FGM/C, it remains a significant harmful tradition for millions of girls and women. In the last few years, renewed efforts to protect girls from undergoing this procedure globally and in immigrant populations have resulted in policy successes. In Great Britain and in other European countries, a groundswell of attention has focused on eradicating the practice among the large immigrant populations of girls and women who have been cut or are at risk of being cut. Moreover, in 2012 the 67th session of the UN General Assembly passed a resolution urging states to condemn all harmful practices that affect women and girls, especially FGM/C. The UN resolution was a significant step toward ending the practice around the world.

In the United States, efforts to stop families from sending their daughters to their home countries to be cut led to a 2013 law making it illegal to knowingly transport a girl out of the United States for the purpose of cutting. FGM/C has gained attention in the United States in part because of the rising number of immigrants from countries where FGM/C is prevalent, especially sub-Saharan Africa. Between 2000 and 2013, the foreign-born population from Africa more than doubled, from 881,000 to 1.8 million.3

In 2013, there were up to 507,000 U.S. women and girls who had undergone FGM/C or were at risk of the procedure, according to PRB’s data analysis. This figure is more than twice the number of women and girls estimated to be at risk in 2000 (228,000).4 The rapid increase in women and girls at risk reflects an increase in immigration to the United States, rather than an increase in the share of women and girls at risk of being cut. The estimated U.S. population at risk of FGM/C is calculated by applying country- and age-specific FGM/C prevalence rates to the number of U.S. women and girls with ties to those countries. A detailed description of PRB’s methods to estimate women and girls at risk of FGM/C is available.

Just three sending countries—Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia—accounted for 55 percent of all U.S. women and girls at risk in 2013 (see Table 1). These three countries stand out because they have a combination of high FGM/C prevalence rates and a relatively large number of immigrants to the United States. The FGM/C prevalence rate for women and girls ages 15 to 49 is 91 percent in Egypt, 74 percent in Ethiopia, and 98 percent in Somalia. About 97 percent of U.S. women and girls at risk were from African countries, while just 3 percent were from Asia (Iraq and Yemen).

Top 10 Countries of Origin

| U.S. Women and Girls at Risk of FGM/C | |

|---|---|

| All Countries of Origin | 506,795 |

| Egypt | 109,205 |

| Ethiopia | 91,768 |

| Somalia | 75,537 |

| Nigeria | 40,932 |

| Liberia | 27,289 |

| Sierra Leone | 25,372 |

| Sudan | 20,455 |

| Kenya | 18,475 |

| Eritrea | 17,478 |

| Guinea | 10,302 |

| Other Countries of Origin | 69,981 |

Source: Population Reference Bureau. Estimates are subject to both sampling and nonsampling error.

Girls under age 18 made up one-third of all females at risk of FGM/C in 2013. While some of these girls were born in countries with high prevalence rates, the majority are U.S.-born children of parents from high-prevalence countries. Anecdotal reports tell of U.S.-born girls being cut while on vacation in their parents’ countries of origin and of people traveling to the United States to perform FGM/C on girls here.5

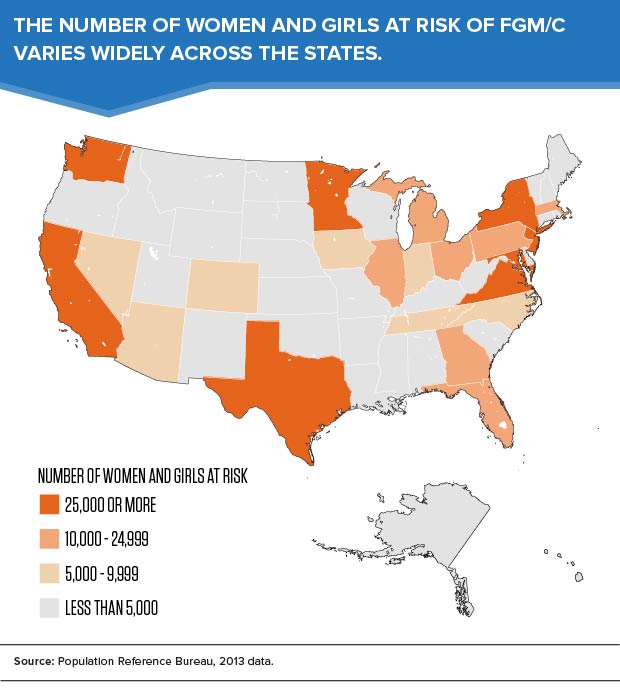

The number of women and girls at risk varies widely across different states (see map). In 2013, about three-fifths of all women and girls at risk of FGM/C lived in eight states: California, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. California had the largest at-risk population (57,000), followed by New York (48,000), and Minnesota (44,000). Minnesota has a disproportionate number of women and girls at risk of FGM/C because of its large Somali immigrant population, estimated at more than 31,000 in 2013. See the number of women and girls at risk in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

While the population at risk is still highly concentrated in large “gateway” states, many immigrant families have fanned out from traditional immigrant gateways to new destinations around the country. Some states also receive large numbers of African refugees. In fiscal year 2014, one-fourth of the 70,000 refugees arriving in the United States were from Africa.6

Most women and girls at risk of FGM/C are living in cities or suburbs of large metropolitan areas. In 2013, 40 percent of the population at risk lived in five metro areas: New York, Washington, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Los Angeles, and Seattle (see Table 2). See a list of the 50 metropolitan areas with the largest at-risk populations.

Top 10 Metropolitan Areas

| U.S. Women and Girls at Risk of FGM/C | |

|---|---|

| All Areas | 506,795 |

| New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA | 65,893 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | 51,411 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | 37,417 |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA | 23,216 |

| Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | 22,923 |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA | 19,075 |

| Columbus, OH | 18,154 |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | 16,417 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | 15,854 |

| Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH | 11,347 |

| Other Metro Areas | 216,307 |

| Outside of Metro Areas | 8,780 |

Source: Population Reference Bureau. Estimates are subject to both sampling and nonsampling error.

With the rise in international migration, the lines between issues facing women and girls in the U.S. and developing countries are blurred. Although FGM/C prevalence rates have held steady or declined in many African countries in recent years, the number of women and girls at risk of FGM/C in the United States is expected to increase in the future, as the foreign-born population from Africa increases.

Given the rapid growth of the youth population in developing countries, improving the well-being of girls has become a priority for many international organizations that promote gender equality and higher standards of living across the globe. Ending harmful practices against women and girls in developing countries could have a measurable impact on the well-being of immigrant families around the world.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Kelvin Pollard and Donna Clifton at PRB for their assistance with the data analysis, and Howard Goldberg and Paul Stupp of CDC for their collaboration on the methodology. We are grateful to the Wallace Global Fund for providing funding for PRB’s work on this topic.