Heidi Worley

Former Program Director

February 24, 2015

Former Program Director

(February 2015) Less than a generation after the genocide in Rwanda that claimed 1 million lives, left 2 million displaced, and destroyed health systems, Rwanda today has been hailed as one of the few countries on a fast track to reducing child and maternal mortality—thus meeting two of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals in 2015.

Rwanda’s maternal mortality ratio decreased by 77 percent between 2000 and 2013 and currently stands at 320 deaths per 100,000 live births.1 Under-5 child mortality has been reduced by more than 70 percent and is well on the way to meet the goal of 54 deaths per 1,000 live births.2

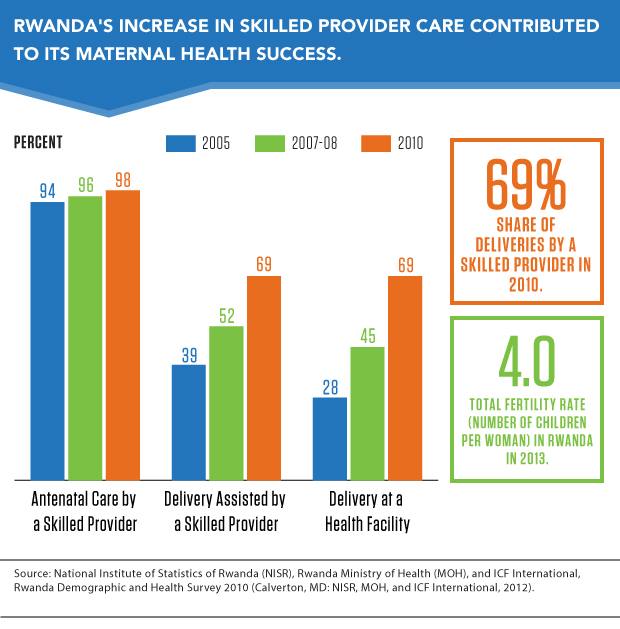

Many factors created this success story. The increase in skilled providers during childbirth over a decade has been especially important for women; and for children, improvements in immunization coverage and exclusive breastfeeding are important factors.

After the genocide, Rwanda faced a severe health worker shortage, as well as limited health infrastructure and high rates of maternal and child mortality. The government prioritized reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health as a way to rebuild basic systems and services through several complementary policies:

Declines in maternal mortality are linked to skilled birth attendance and improvements in the contraceptive coverage rate. Rwanda bolstered its workforce to address maternal and child mortality. By 2012, there was one doctor per 16,000 people and one nurse per 1,300 people. Before 1997, Rwanda had no trained midwives, but now there are around 1,000.3 Rwanda established new standards for quality of care, and in 2010, delivery by a skilled provider was at 69 percent, as was delivery in a health facility (see figure).

The government decentralized the health sector to strengthen community involvement and trained 45,000 community health workers to provide primary health services at the village level. Elected by their community, these workers connect communities to health services, especially in remote areas, and monitor health at the village level. Each village elects three volunteers who are trained by the Ministry of Health: a male and a female, who are in charge of integrated case management of childhood illness and family planning; and a female who is in charge of maternal and newborn care. They all play a key role in expanding the coverage of family planning, antenatal care, and childhood immunization, and they also provide services for malaria, pneumonia, and diarrheal diseases.

Rwanda’s national performance-based financing system rewards community health workers according to selected indicators, including the proportion of women delivering at health facilities and the percentage of children receiving a full course of basic immunizations. Such incentives have helped boost the use of maternal and child health services, according to Paul Farmer, a U.S. physician living in Rwanda, known for his work with underserved populations.4

Rwanda’s government is committed to providing universal health care as part of its Vision 2020 Strategy. Since 2000, the core of this commitment has been its community-based health insurance scheme known as Mutuelle de Santé. The system lowers catastrophic out-of-pocket payments and ensures access for vulnerable populations, focusing on maternal and child health services.

Community committees are responsible for mobilizing and registering members, collecting fees, and clearing bills from health facilities. Annual premiums are based on wealth categories. Ambulance transport is also covered, thus reducing a significant barrier to emergency care for pregnant women who have complications.5 With specially programmed mobile phones, community health workers can contact health facilities for referrals.

From 2000 to 2007, growth in use of health services was greatest among the poorest people. Health insurance was made compulsory in 2008 and by 2012, 90 percent of the population had enrolled.6

Hand-in-hand with its comprehensive insurance program, Rwanda has adopted a number of innovative tools to strengthen its health systems. All maternal and child health services are integrated under one national monitoring and evaluation framework to improve priority setting, planning, and resource allocation. Rwanda has developed a web-based Health Management Information System to collect data from a variety of sources and has scaled up maternal death reviews as part of their efforts to strengthen data collection.7

The success story in maternal health is also a story about increased family planning coverage. Modern contraceptive prevalence increased in Rwanda from 4 percent to 45 percent in 10 years. Research shows that family planning can prevent as many as one in three maternal deaths by allowing women to delay motherhood, space births, avoid unintended pregnancies, and stop childbearing when they have reached their desired family size.

Rwanda’s total fertility rate decreased from 6.2 children per woman in 1992 to 4.0 in 2013.8 Community health workers have much to do with these successes. They can provide condoms, pills, injectables, and cycle beads. The fast-improving uptake of maternal health services has been linked to a strong positive response to community health workers; the push to subscribe to the community-based insurance scheme; and an effective public education campaign that reached three-quarters of women, supported by a system of fines imposed on those who fail to attend antenatal care and deliver in health care centers.9

Rwanda still faces challenges. The country needs 586 more midwives to reach 95 percent skilled birth attendance.10 Rural areas are still underserved: Forty percent of women live more than an hour away from a health facility. Even with the increase in family planning and decline in the total fertility rate, contraception remains unavailable to or underused by many Rwandans. And nearly one in every two children under 5 are stunted.

In 1995, most development agencies were ready to give up on Rwanda, then one of the poorest and most vulnerable countries in the world. But now, Rwanda is one of the few countries on track in 2015 to meet the Millennium Development Goals for reducing child and maternal health.